The Outlook of Shipping Industry in 2017 and Beyond

The maritime world eventually passed the 2016, a year that was full of colossal losses and huge harms.

src="/files/fa/news/es/Thumbnails/512dccb6-a092-4202-88d8-f6e5dc83fcee_260_199.png' class='img_convert' title='The Outlook of Shipping Industry in 2017 and Beyond' alt='The Outlook of Shipping Industry in 2017 and Beyond'>

In this context, the ship building industry does not seem to have a bright future in the coming years. Most of the newbuild orders are being delivered and nearly no new order is made. According to Danish Ship Finance, the number of active shipyards have fell from 1140 in 2010 to 630 in 2016, and 290 other shipyards will be at the verge of closure after 2016.

In this context, the ship building industry does not seem to have a bright future in the coming years. Most of the newbuild orders are being delivered and nearly no new order is made. According to Danish Ship Finance, the number of active shipyards have fell from 1140 in 2010 to 630 in 2016, and 290 other shipyards will be at the verge of closure after 2016.

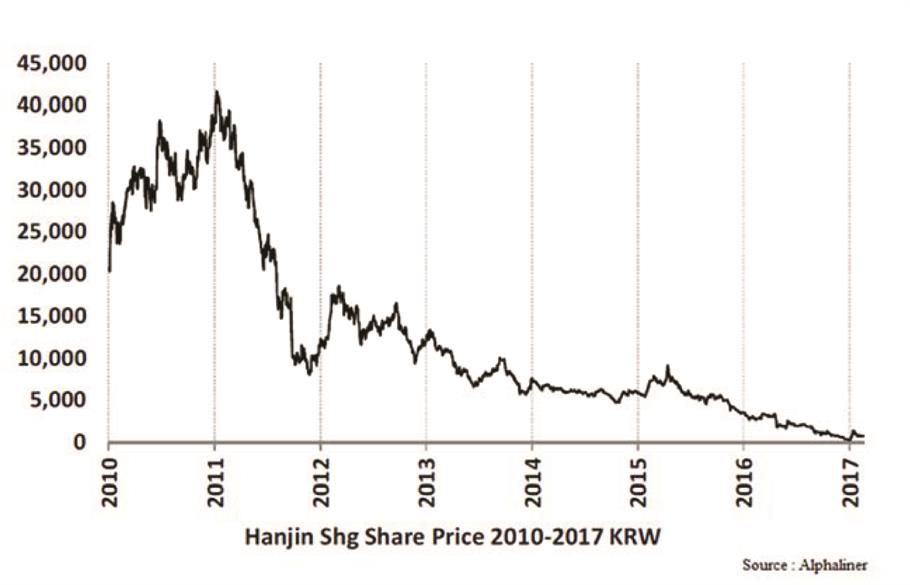

The year was full of surprises from the annihilation of giants like Hanjin in the industry, to imbibing of other giants in terms of mergers (NYK, MOL, and K Line), acquisitions (UASC, NOL, and Hamburg Süd), or even alliances (HMM).The freight rates fell historically to their lowest levels in some past decades. As expected, a formidable amount of overcapacity was built up that not only deteriorated the marketplace completely, but also led to unprecedented boost of ship breaking. The slowdown of global economic growth also worsened the conditions for shipping, weakening the revenue stream and incurring 3-billion dollars of loss for the industry.

The year 2017 began with slow recovery in the market, bringing some improvement to prices in main trade lanes. Yet as trends indicate, the slight improvements do not have the momentum to transform the current trends of the global markets. This is indeed an outcome of the socioeconomic and political factors that are influencing both the supply and demand in the shipping industry and its context in the realm of international trade. A brief review on some key trends can be useful.

The Demand for the Shipping industry

Global economy growth

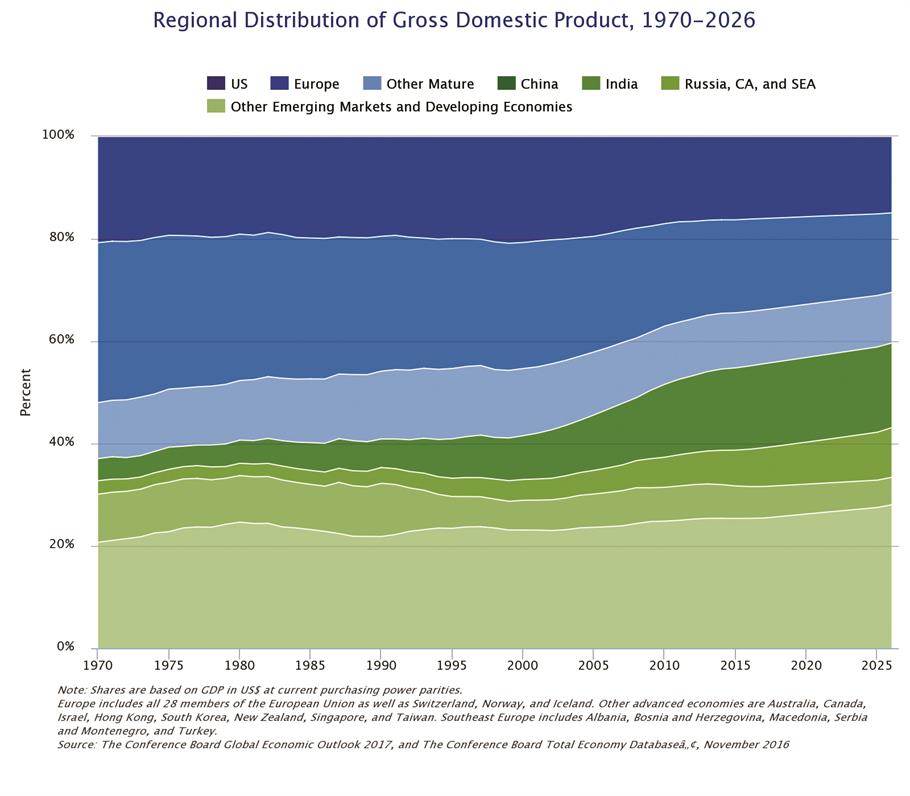

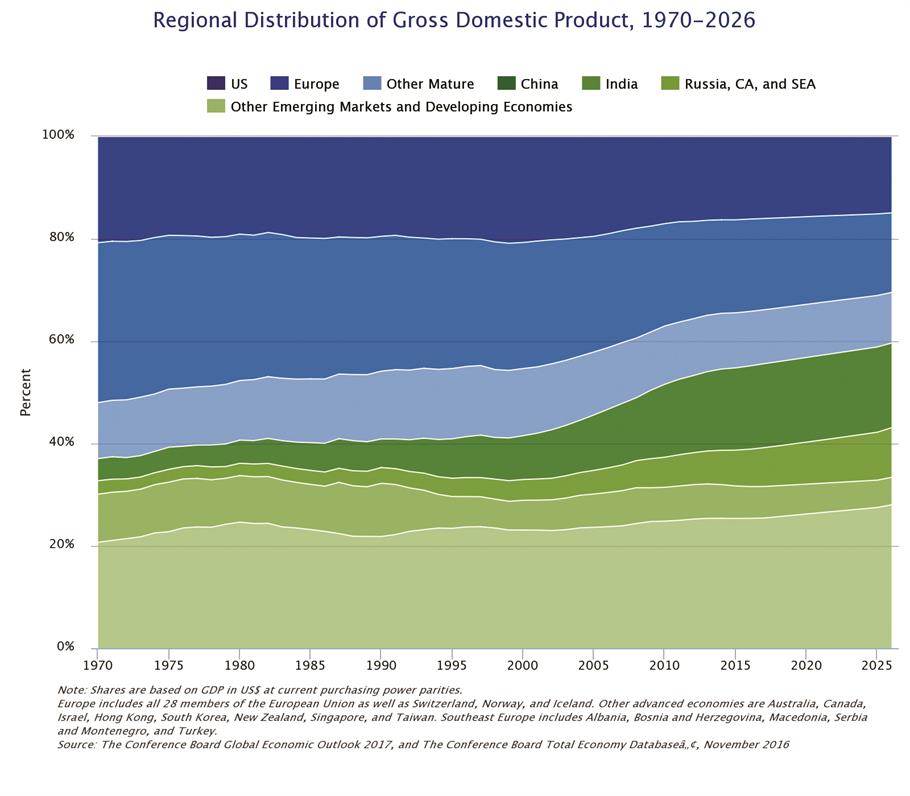

The world economic growth is experiencing a significant slowdown. According to the World Bank the global economy is estimated to grow around 2.7% this year, in comparison to the 2.3% growth in the past year (the lowest recorded figure since the global financial crisis). With projected growth rates that are under 1.8% in the coming four years, the advanced economies of the world in US, EU, and Japan are afflicted with an economic stagnation that is a result of lowered productivity growth, heightened policy uncertainties, tepid investments, and lack of external demand. On the contrary, the Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs) are taking the momentum in the global economy context by average annual growth rates between 4.2 to 4.7% within the coming four years. Yet as EMDEs are encountering with problems in terms of subdued investments, their economic growth will continue to be sluggish in the coming decade. This trend will contribute to the worldwide lessening of international trade and investments in infrastructure developments. It will also strengthen the imbalance in trade between the developing and the developed countries.

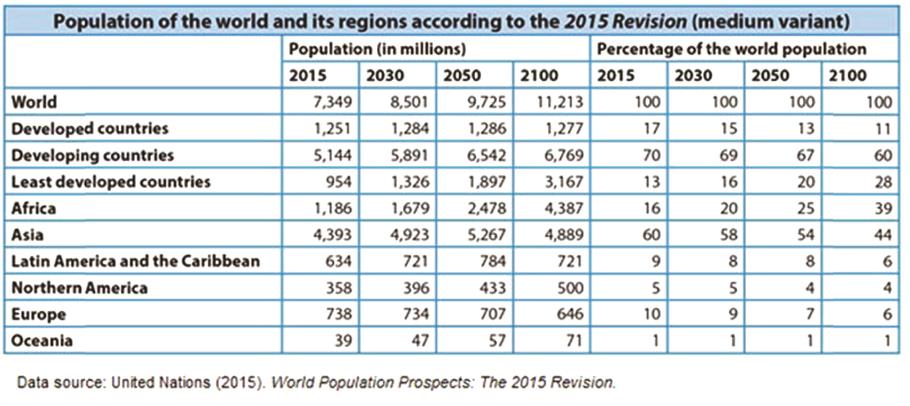

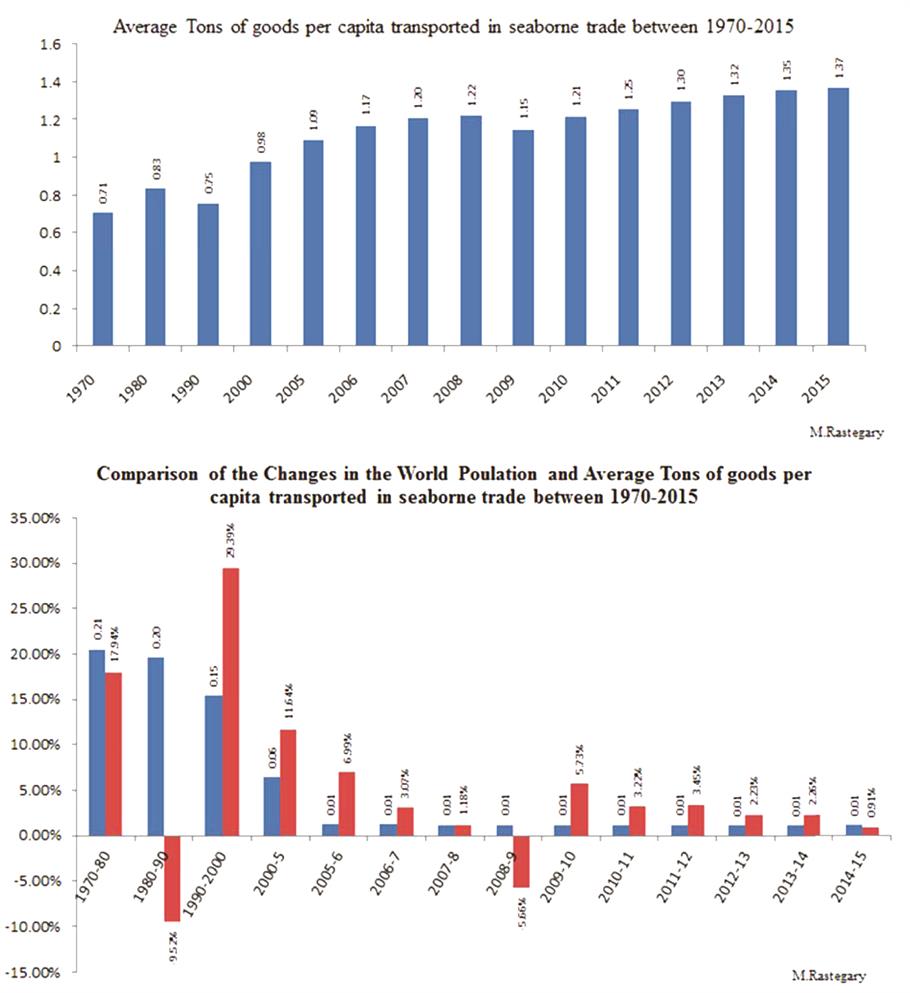

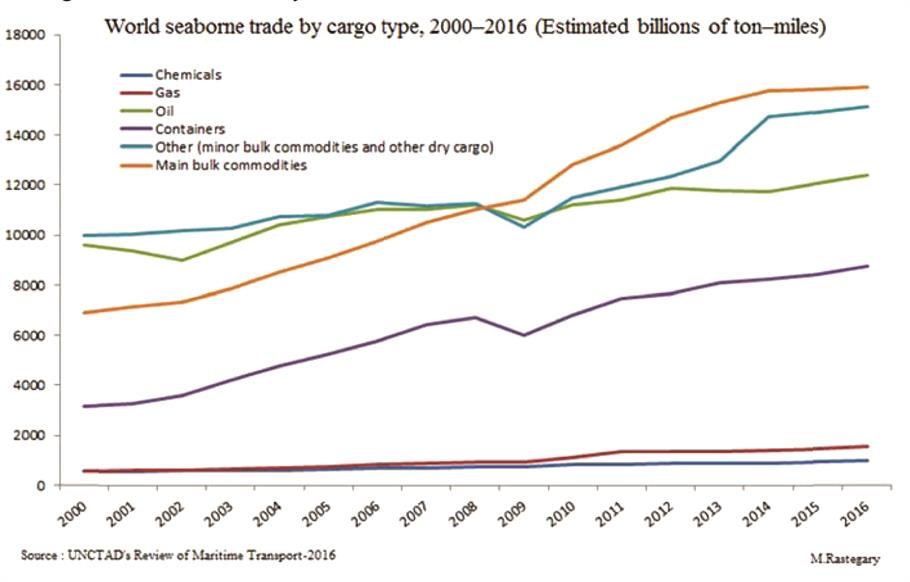

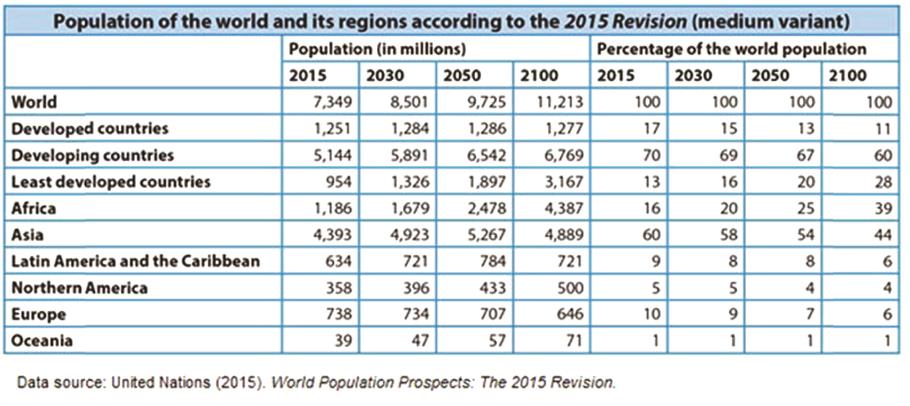

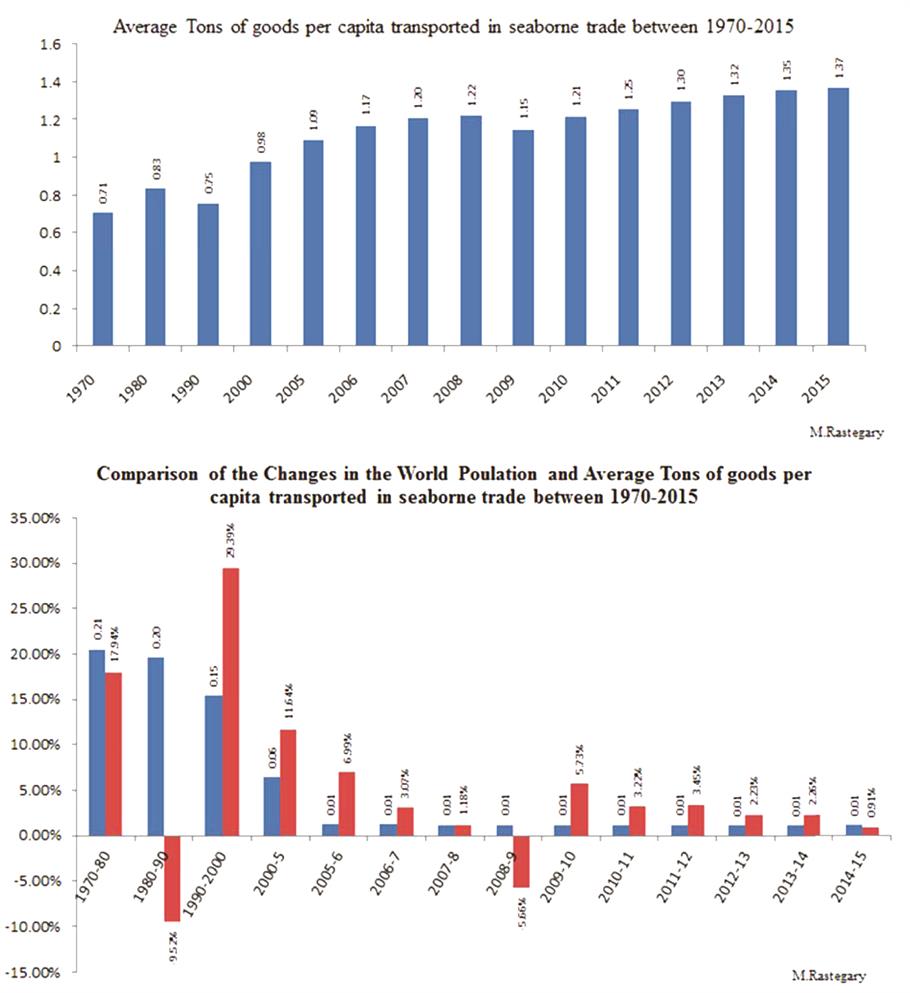

This is happening in a world that is getting more populated day by day. By 2030, the population of the world is estimated to grow to 8.5 billion. Between 2015 and 2030, 2.1 billion people will be born, 2-billion children will be at school age, 1.9 billion people will enter their youth, 1.1 billion people will be added to the population of city dwellers in the world, and 1 billion people will enter into their old age. Although it may seem that more population in the world will imply a boost in the shipping businesses, by noticing the concentration of 85 percent of the world population in the developing and the Least Developed Countries along with the growing age of population in the developed countries, it can be envisaged that trend can faintly overcome the structural deficiencies of the global economy. Indeed it can be evidently seen that after the global financial crisis, the globally average seaborne trade per capita has only grown 15% between 2007 and 2015. That is while the growth between years 2000 to 2007 has been 22.45%.

One emerging trend that can act as a major driver of inequality gap in economic development of nations is protectionism. Protectionism directs the states away from the globalized economy and focuses on maximization of national interests of a state by adopting a zero-sum mindset. This approach can lead to reshoring and decline of shipping markets in short terms, and deterioration of prevailing economic sets in mid-terms. Apparent instances were BREXIT, and D.Trump’s election as the president of United States. The same discipline may also arise in states like France and Netherlands in near terms.

The anemic economic development of the developed countries is also weakened by politicized movements that act against the augmentation of an integrated global economy. Such actions ruin the global trade and the globalization context. One eminent instance can be found in the economic sanctions against nations (e.g. Islamic Republic of Iran, Russian Federation, etc.), warmongering in different parts of the world (e.g. Yemen, Syria, Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan, etc.), rescinding global trade treaties ( e.g. NAFTA, or TPP), intentional obstructions to participation of other states in the global trade ( e.g. membership of Islamic Republic of Iran in WTO), etc. Such harmful actions deteriorate the status of global economy and kill international trade as the main fosterer of the shipping industry.

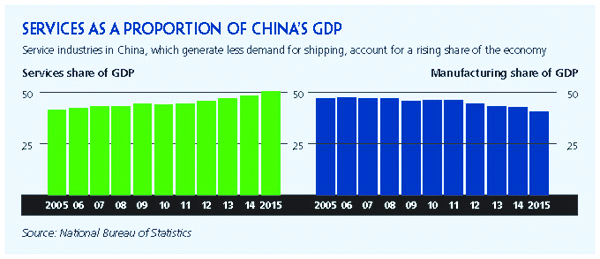

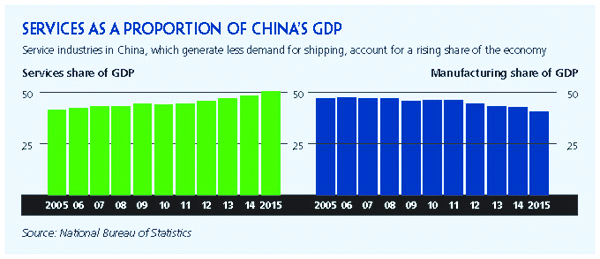

The other trend that can affect the shipping industry in the coming decade is the maturing of developing economies: as the economic development progresses in such states, the share of construction and manufacturing sectors in their GNP is reduced and the share of services in their GNP rises. This usually leads to the reduction of imports of raw materials and capital goods in them. China may be an instance of this trend in the coming years.

Finally, commitment to sustainability of economic development and the technological developments in this regard may transform some principal supply chains. For instance, use of clean and renewable resources of energy (e.g. Solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal, etc) can have significant effects on the prevailing demand for energy commodities. The implemented policies for power generation in EU are among the significant instances of this trend.

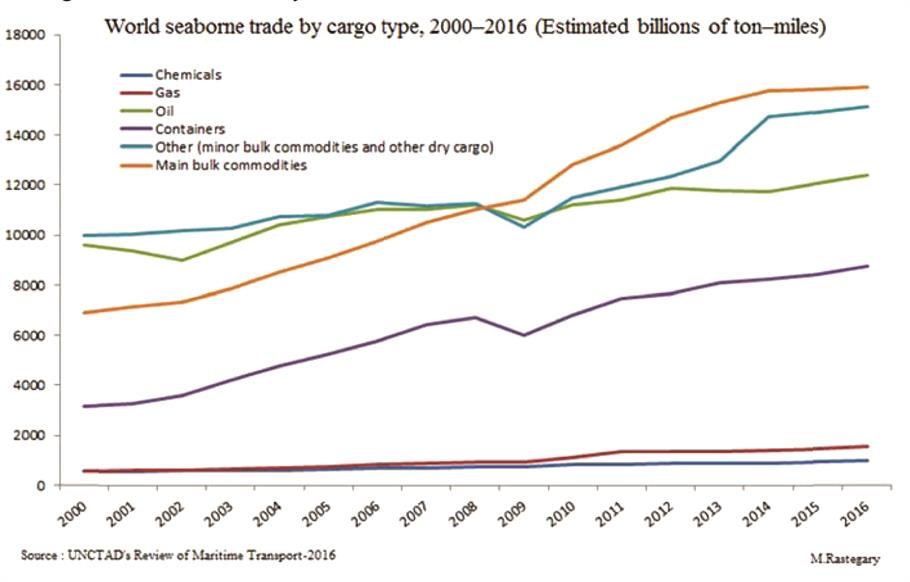

Average haul and ton-miles

The established shipping routes in the main trade lanes have been unchanged for some decades and the average haul figures growth in these years have been mainly a product of growing tonnage of goods in constant mileage. Yet, in the recent years there have been some changes in the trade lanes that can change the average haul in the industry.

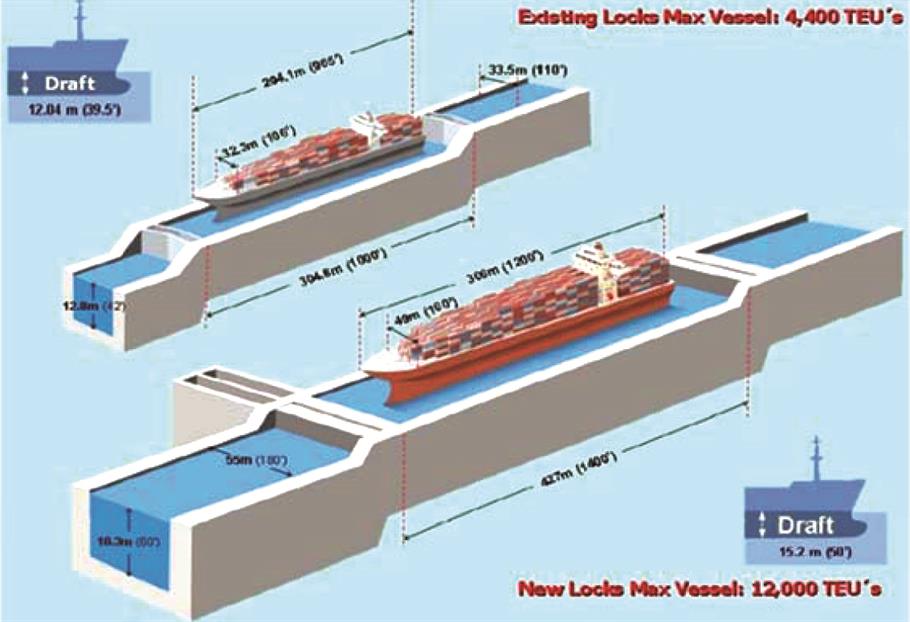

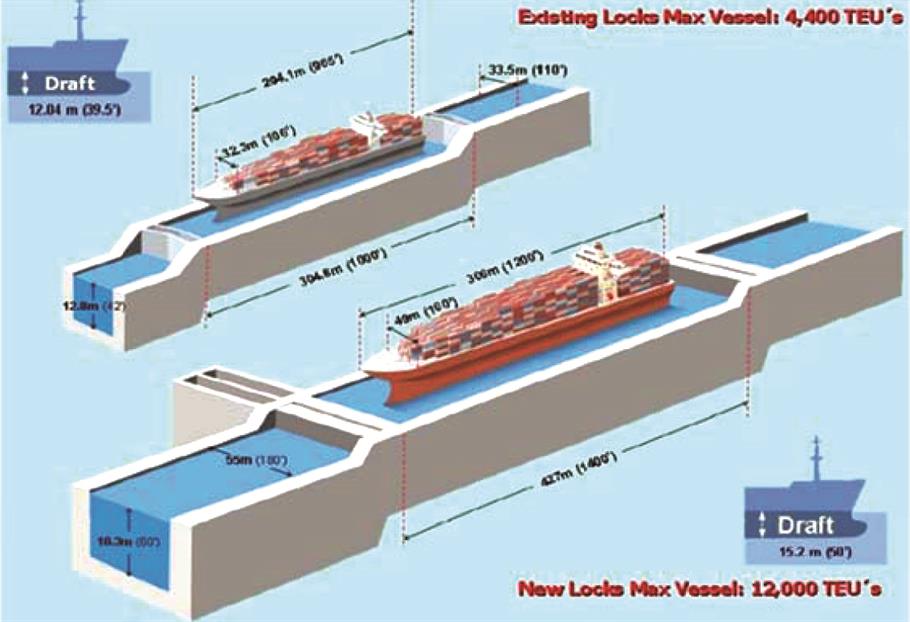

One of the most significant occurrences that can contribute to change in the average haul in the seaborne trade, are the recent expansions in Panama Canal. The Panama Canal expansion that was inaugurated in early 2016, practically took the seaborne trade to the next level. The new canal facilitates the passage of the New Panamax ships (120,000 DWT, with a capacity of 12800 TEU in the cellular vessels) between Atlas and Pacific oceans. As Panama Canal shortens the distances of American, European, and Far East ports, deployment of bigger ships can mean that the 144 trade routes that pass this canal can attract more trade, being seen as cost efficient alternatives for the competing longer East-West trade routes.

Moreover, the ship size growth and shipping market arrangements in the maritime container trade have pushed the supply chains towards extending the Hub and Spokes networks in ports. This implies that in most cases, the transshipment of goods between the ports will incur a larger needed mileage to deliver them in a gateway port. It should also be noted that the cascading of bigger ships to smaller ports will increase the need to transshipment, and is expected to increase the average haul.

Facilitation of the bigger ships by Panama Canal Expansion

The other influential factor is the competition from alternative modes of transport: a prominent instance is the 12000-Km Eurasian land bridge that connects Yi wu in the Eastern China to London in the Western end of Europe in terms of One Belt- One Road scheme. Although the new rail corridor cannot compete with the maritime transport in terms of costs, it has great advantages in terms of time and delivery. Such mode alternatives can take part of the shipping traffic away. For instance, the Eurasian Land Bridge is estimated to attract 100,000 TEU of the container trade between EU and Far East, which will affect the average haul of the maritime container trade in the East-West trade lane.

The Eurasian Landbridge was inaugurated in January 2017

The other trend that can affect the average haul in shipping arises from the possible security issues in shipping routes and their chokepoints. This includes the risks and perils of piracy, possible terroristic actions, military conflicts, and wars. The instances of such high security risks can be seen in Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean, African side of Atlas Ocean, and Eastern bounds of Mediterranean Sea.

Transport Costs

There are several trends that will affect the transport costs in the coming years. First of all, the ship size growth trend that has targeted economy of scale in the sea, practically has raised diseconomy in ports. This trend has caused essential needs for capacity development in ports which cannot keep pace with the developments of shipping in terms of time. This usually ends in shortage of port capacity in short terms and added costs both in the short and long run. In container shipping which is the more competitive part of the industry, this trend also exacerbates the need for hub and spokes networks which involve the addition of the transshipment costs (and the costs of delay in delivery of goods) to the overall transport costs in the supply chains of the regional hinterlands.

Some shipping lines are also inclined to monopolistic behaviors in the markets. This will increase the dissatisfaction and resistance of the stakeholders in supply chains ) i.e. the governments, the consumers, the tax payers, the manufacturers, etc.) and motivate them to react to such measures and arrangements that can contribute towards higher transport prices or more concentration in the industry. Among the instances we can point to the measures of People’s Republic of China to proscribe the establishment of P3 alliance in 2014, and several anti-trust investigations and fines by FMC (US), PRC, and EU in the recent years.

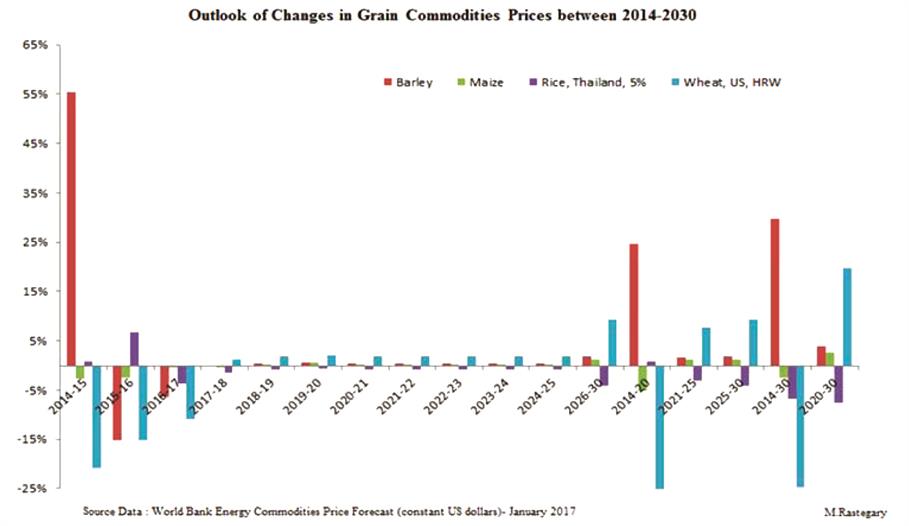

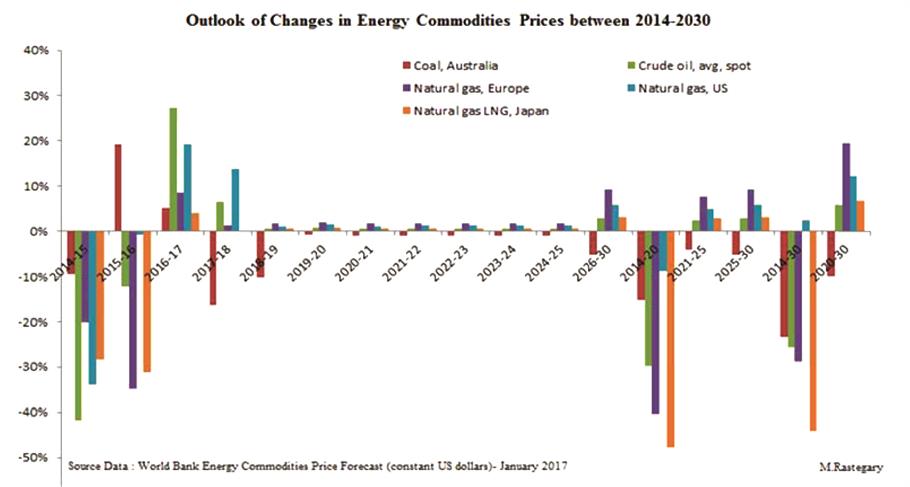

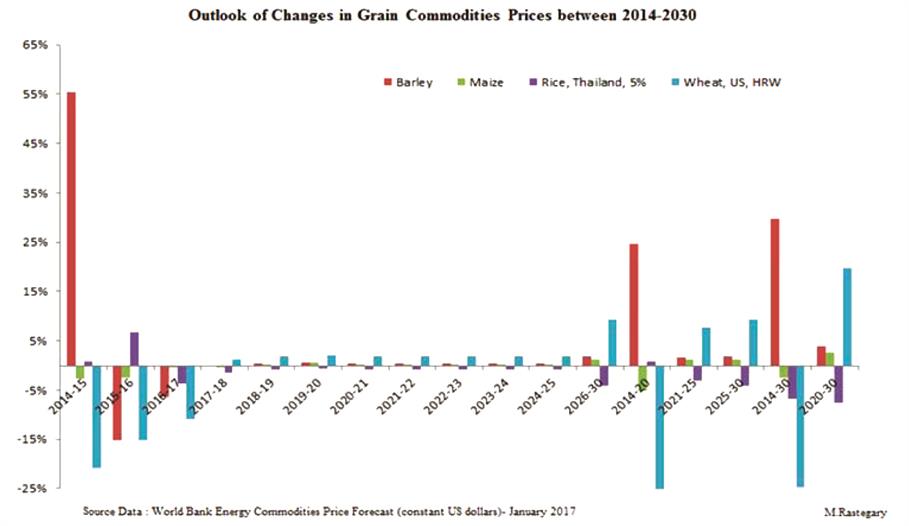

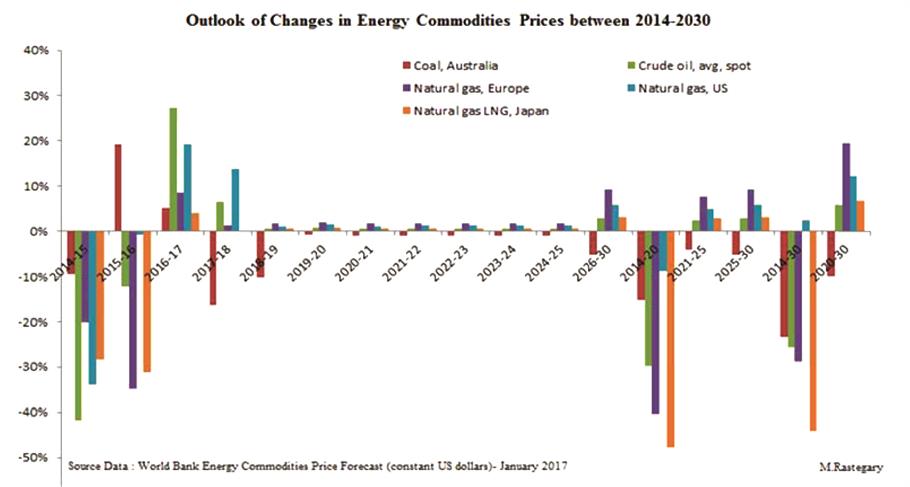

On the other hand, after the sharp fall in 2014, the forecasted outlook of commodity prices in the coming decade indicates very modest growth rates. This is due to technological achievements in production, abundance of supply, and highly competitive commodity markets. Taken as a consistuent of the commodity price, the transportation costs of them will have a little margin for growth in the coming decade. This is another implicit barrier to increase the revenue of shipping lines. This will happen in an industry that is already stuck in oversupply and is striving to maximize her revenue and cash flow.

The mentioned trends indicate that the rate of growth in the prevailing and future demand for the shipping industry is small, uncertain and volatile.

Random shocks

According to G.Leonhard, human will see more changes in the two coming decades than the past 300 years. Some of these changes will be shocking to the societies and their industries. Shipping is no exception to this and it will be certainly susceptible to some shocks in the context of her business. These shocks have the capacity to disrupt the businesses and involve the firms and the industry in a number of unforeseen and unwanted consequences on both the demand and the supply hands. Among such unforeseen shocks, we can point to the following:

* Political Shocks- The rise of the inward protectionism in US, UK, and some other developed countries has been a shock that can affect trade and investment throughout the world. A vast series of disrupting consequences can be perceived in this context that can include reshoring or near-shoring of industries, significant changes in the trade balance of countries, rescinding of trade treaties, disrupting military conflicts, wars, etc. In this sense, the phenomenal election of D.Trump as the president of the United States and the unpredictability of his administration can be seen as the shock-generating machine for the industry.

* Natural disasters- natural disasters are seen as a main disrupting factor for supply chains in the 21st century. This is a trend that will be aggravated by furthering of climate change. The natural disasters can harm the production origins, affect the targeted markets, destroy the logistics infrastructure, and disrupt the flow of goods, information and cash in the supply chains. According to the Eventwach report, in 2016 all of top 5 significant disrupting events in supply chains have been among natural disasters ( specifically typhoons, and earthquakes) that have incurred an aggregate revenue loss of 37 billion USD in the global level.

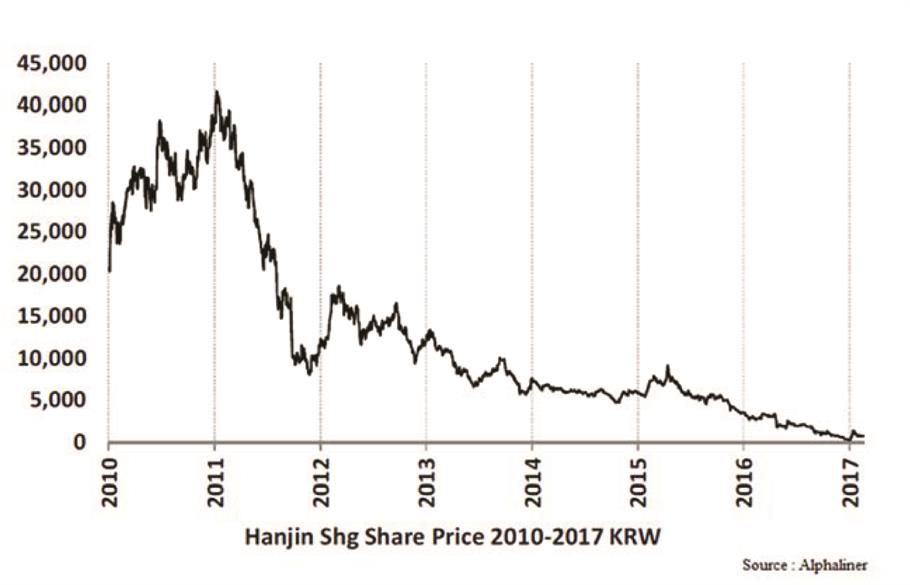

* Financial shocks- the 21st century has been a new era for financial shocks. While the world is still recovering from the global financial credit crisis, the nations as well as international businesses are encountering an increasing number of financial shocks. Among the crucial financial shocks, we can point to the financial challenges of Greece as the leading ship owner state in the world. There are multitudes of micro-economic level financial shocks that can afflict the industry in the coming years. Insolvency of Hanjin shipping in 2016 was an instance of the possible ground breaking financial shocks in the industry and their acute consequences in the global supply chains.

* Piracy- this is another random shock that can risk the entire business of shipping in some tradelanes. According to ICC IMB Annual Report in spite of 35.7% reduction in a 5-year period, the shipping industry have encountered 191 actual and attempted attacks against merchant ships throughout the world. The majority of piracy actions have been taking place in South East Asia, Far East, Eastern and Western African Waters, and South America. The piracy not only involves in larceny of capital assets, liability to cargo interest , and responsibility towards the hostages for the firm, but also entails deterioration of marketplace on the tradelanes, general raise of costs (e.g. the maritime insurance), and ruining the face of shipping as a secure and profitable business in the industry level.

The Supply in the Shipping Industry

In contrast to the vague and volatile demand, the industry is currently consisted of a solid and rigidly in place supply that has been established by heavy investment in the pass of years. In order to have a better understanding of the industry’s supply, let us have a look at some significant trends in it.

Commercial Vessel Fleet Development

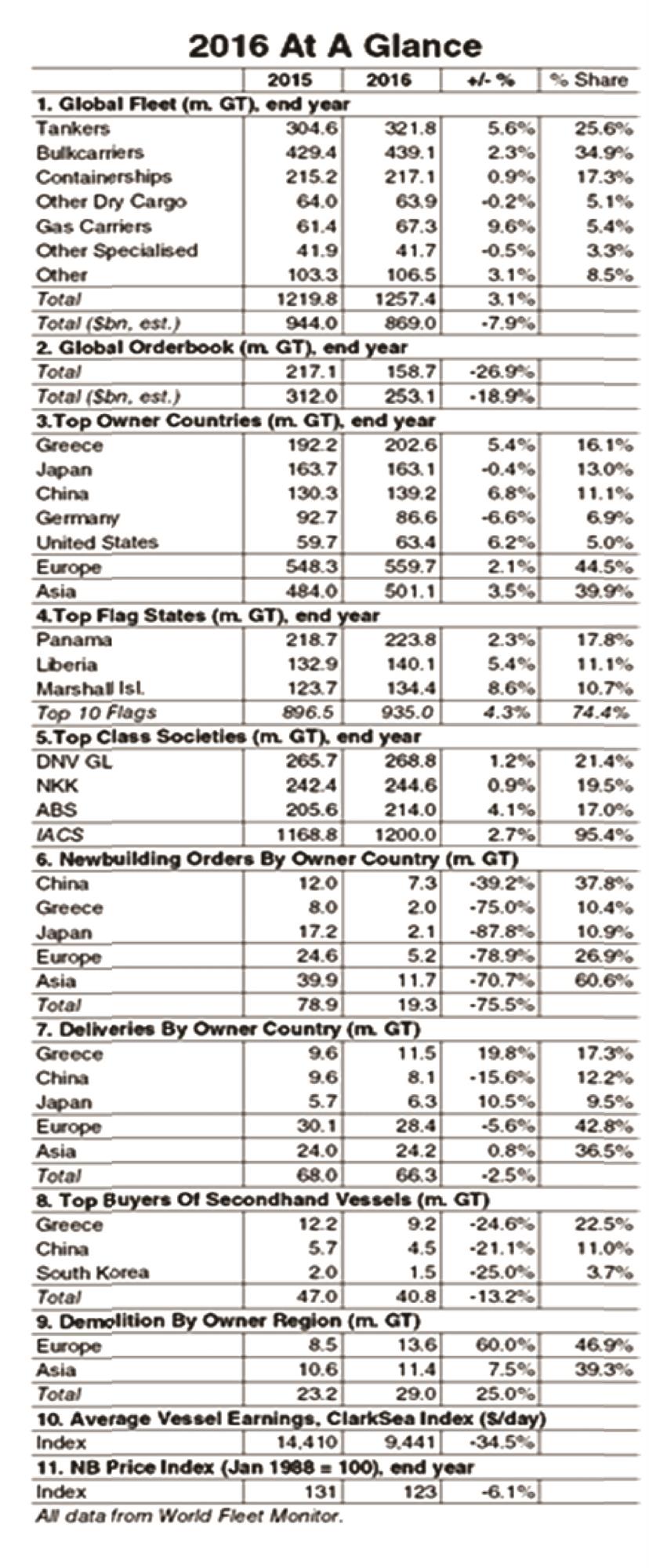

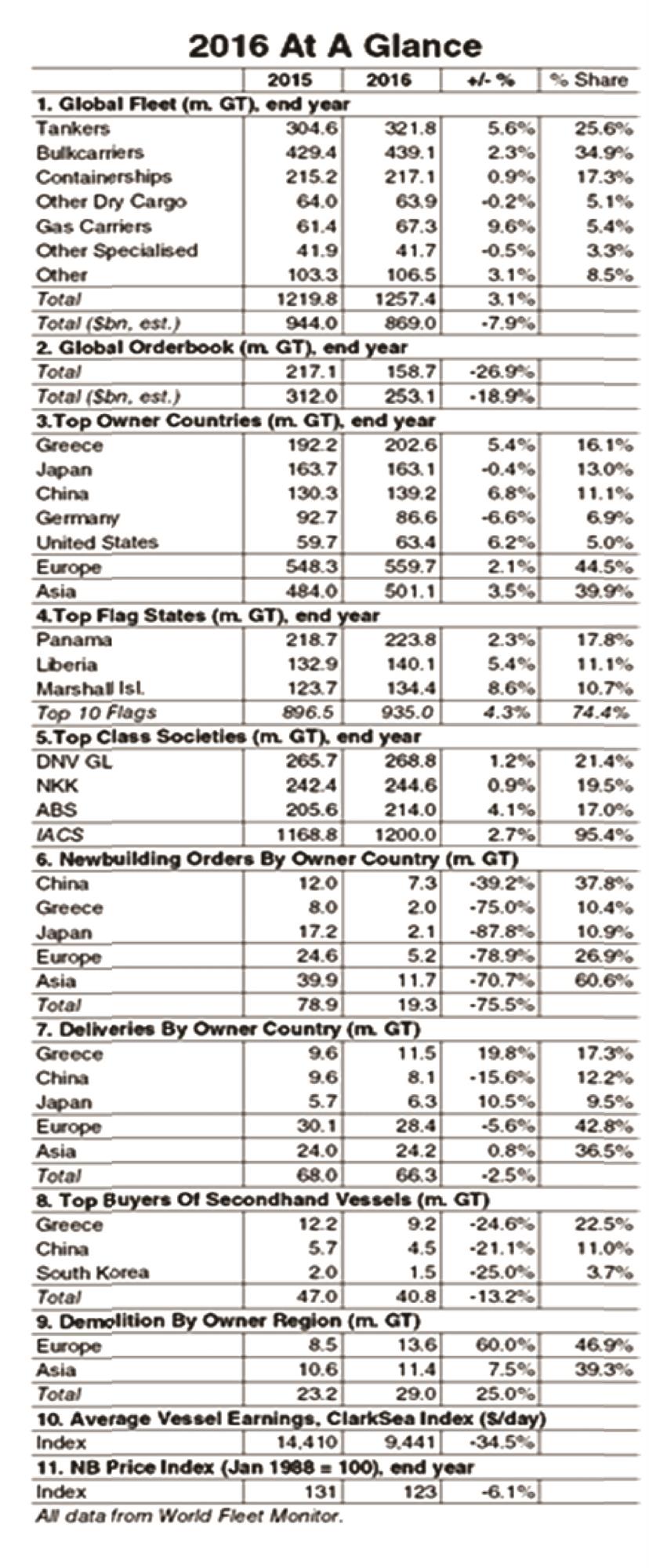

According to Clarkson, at the end of 2016, the global shipping fleet capacity was 1257.4-million GT that indicated a 3.1% rise in comparison to 2015. However the asset value of the global fleet has reduced as much as 7.9%. That is while according to Danish Ship Finance by the end of 2016, 66% of the existing vessels in the global fleet were under 10 years of age, and only 9% of the fleet capacity was older than 20 years.

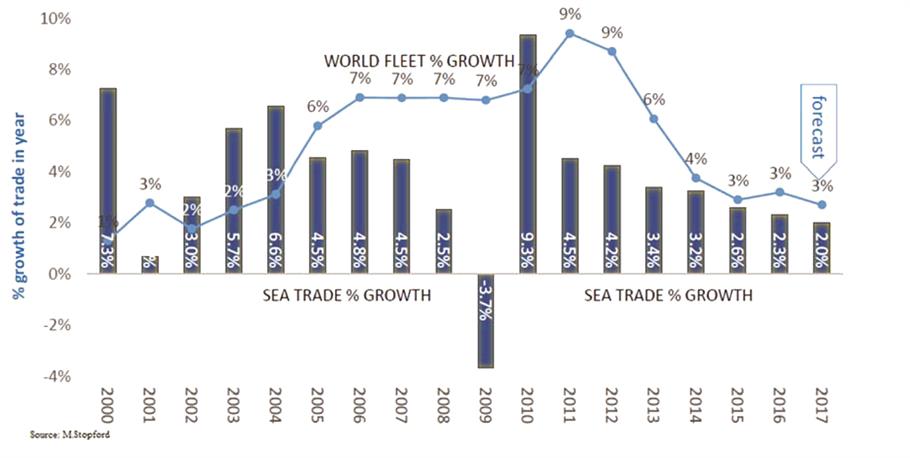

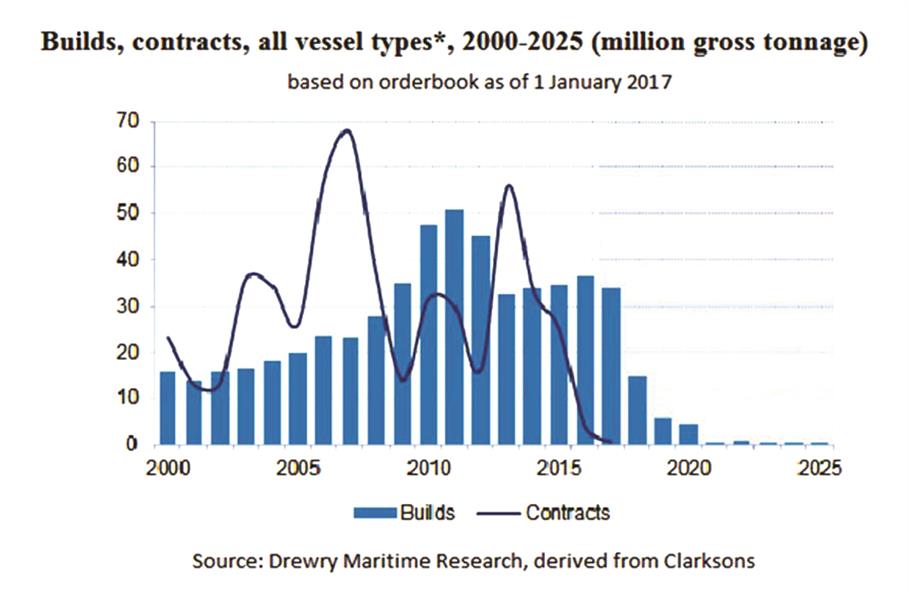

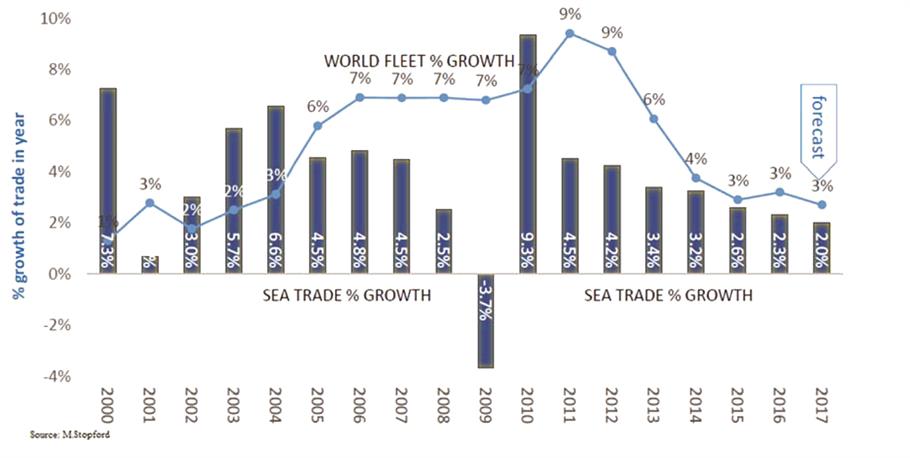

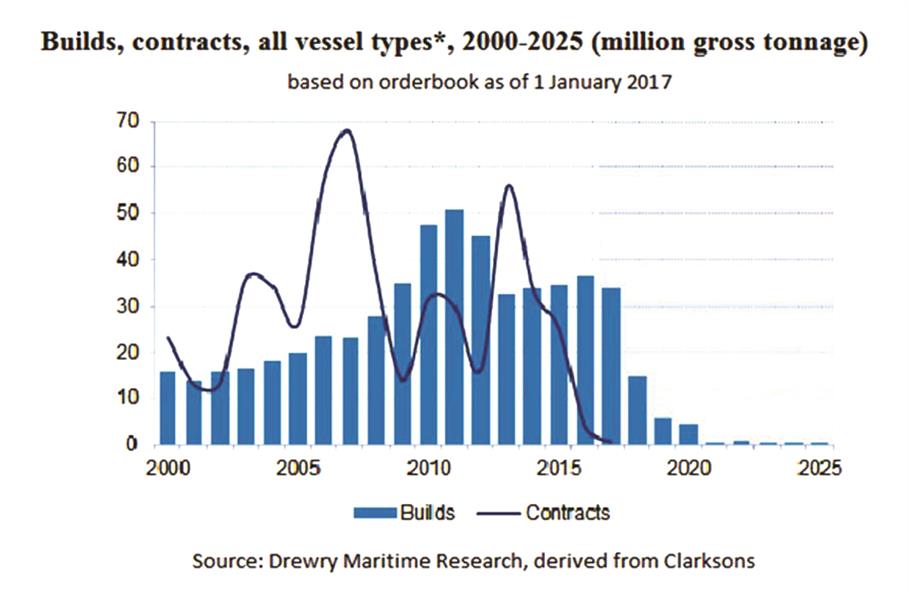

The Shipping industry is encountered with severe overcapacity. Since the early years of the 21st century, the shipping fleet has been growing much faster than the global sea trade growth. According to Dr.M. Stopford, between 2005 and 2016 the industry has been spending between 80-100 billion USD on newbuilds on the annual basis. This has led to buildup of 18 to 20% of oversupply in the global shipping fleet.

In this sense, the industry has been more supply-pushed than demand-driven throughout the past decade. Part of this oversupply has been utilized implicitly by slow steaming from the early 2010s. Similarly in the container market, the shipping lines were engaged in alliances to tackle the load factor issue on the main tradelanes. However by pass of years, the increasing addition of growing orders and newbuilds to the global fleet and the unexpected downturn of demand growth in the global markets negated the control measures and inefficiency began to show up in the entire industry.

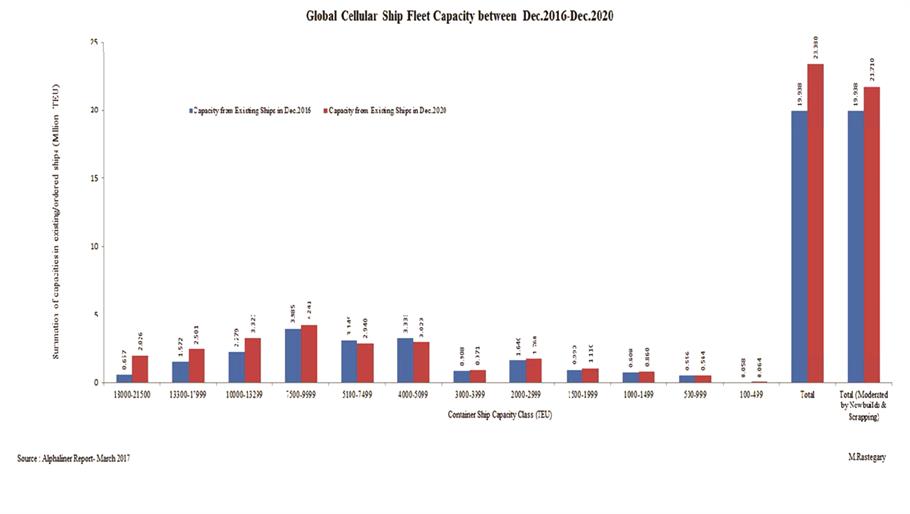

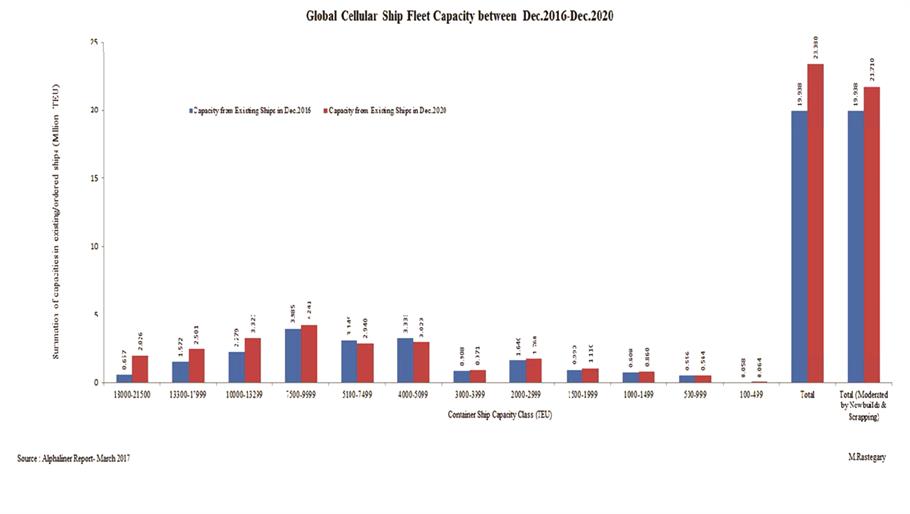

One outstanding trend in the container market was the introduction of Ultra Large Container Vessels (+10,000 TEU) as the more efficient dominant design of cellular fleet and the prolific entrance of ULCV newbuilds to the market since 2013. Although as discussed in my other works, the ship size growth has not proven to enhance the efficiency of container shipping as it was expected, operating the megaships have been considered as a source of competitive advantage in this market. As a result the share of these mega-ships in the global cellular fleet capacity increased to 22.61% and 25.8% in the end of years 2015 and 2016. It is estimated that by the end of 2017, this share will rise to 31.3% and by the end of 2020 it will go further than 36 percent of global cellular fleet capacity.

Shipping Fleet Productivity

As the ship design and the trade routes have not been changing much in the recent years, we can assume that the fleet productivity has not changed much in most segments of the market (i.e. bulkers, oil tankers, general cargo ships, LNG carriers,etc.).Yet, this is not true about the container segment as the introduction of the ULCVs has transformed the market and ship design. Therefore herein, we focus more on the changes in the container fleet productivity in the recent years and the years ahead. In this sense, the fleet productivity has been changing in terms of following g four main determining categories:

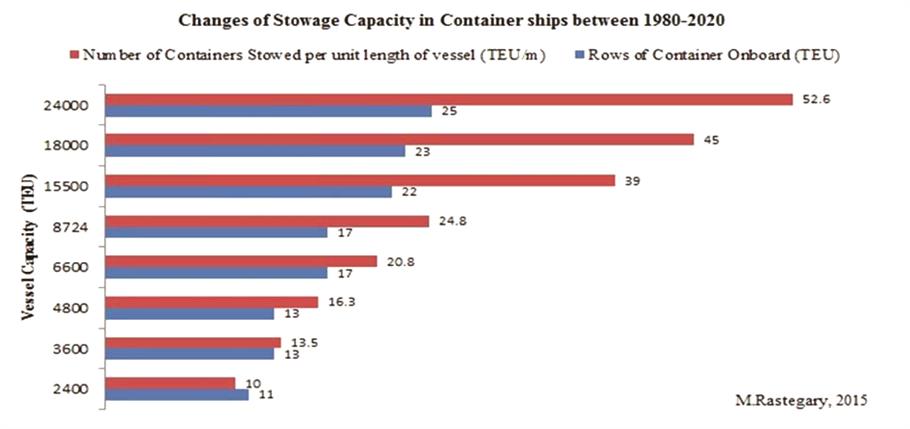

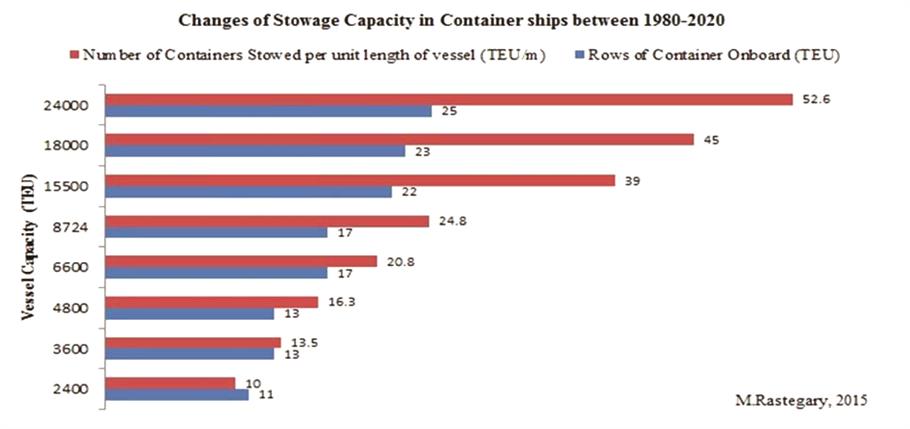

* Deadweight Utilization – The ULCV design has generated significant gains in terms of deadweight tonnage utilization. An 18000TEU-Malaccamax container ship provides the needed stow for 45 TEUs per meter of vessel, that is while the stowage capacities per meter length of a 15500TEU-New Post Panamax. an 8700TEU-Super Post Panamax, and a 6600-TEU Post Panamax Ship are 39, 24.8, and 20.8 TEUs respectively. This is a huge gain in terms of container ship design. However in the real world and in the shades of the rising oversupply and weakening ocean freight demand, the shipping lines have grave problems in terms of filling their ULCVs in ports. In order to tackle this issue, the shipping lines have focused on establishing alliances and forming a more concentrated market.

* Speed – just like the other segments of shipping, the container vessels have been sailing at slow steaming speed (21 Knots) since the global financial crisis in 2007 and 2008. This has been a major saving measure as it cuts the fuel costs and also facilitates the utilization of otherwise oversupplied fleet in the segment.

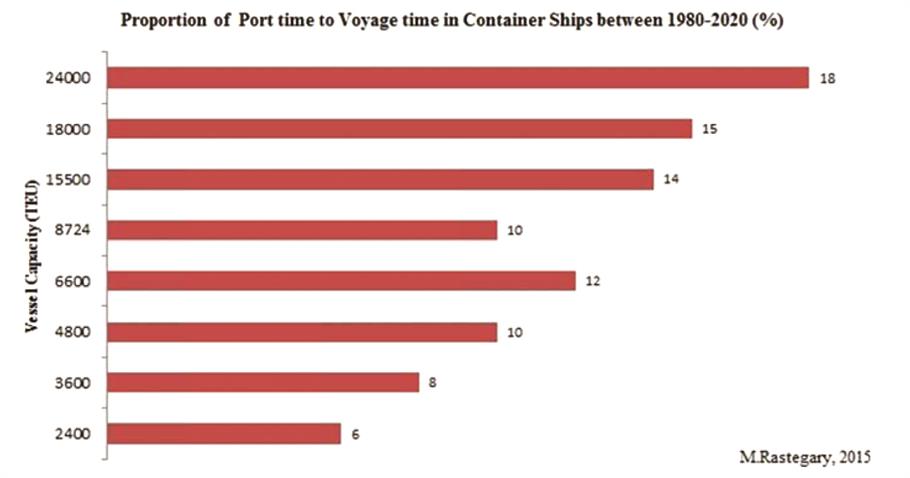

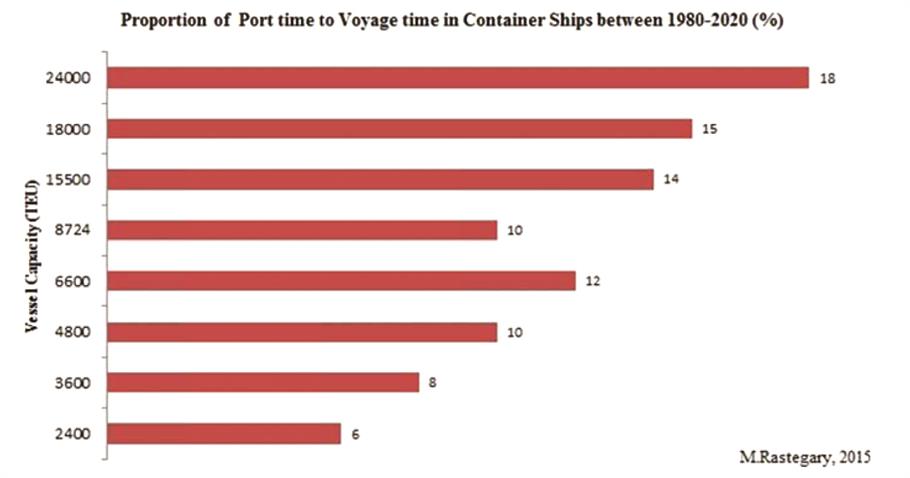

* Port time – As the bigger ship brings a greater volume of cargo into the port, and it consequently needs a bigger port time. This can be seen in the figure below. Also as cited earlier, the economy of scale for larger ships is coupled with dis-economies in port. Indeed the introduction and proliferation of ULCVs have pushed the ports to their challenging limits. As indicated in the other exhibit, I have outlined these challenges in 23 main categories. The resultants of these forceful challenges act towards weaker productivity of the vessels in the ports. It is necessary to remind that as introduction of mega ships is accompanied by cascading effect, the smaller ports will also experience similar problems and the entering bigger ships will be affected by them.

* Productive Days – Entrance of bigger ships in smaller ports ( as a matter of proliferation of ULCVs and the cascading effect) will entail harder navigation and berthing issues, bigger volumes of operations, and ever increasing haste( and risk of mishaps).Obviously these factors reduce the productive days of ships. Furthermore, the highly possible delays in the window of operations in port will affect the window of operations in the next ports enroute, and deteriorate the service reliability of the shipping line.

Balance of Shipbuilding, Scrapping and Losses

The new-build frenzy in the past decade has had a very significant role in formation of the extra-oversupply in the shipping market. The prospect of ship-building demand in the coming years seems to be gloomy and as according to Clarkson Research will be near to zero. The trend is somewhat better in the tanker and LNG segment as the demand in global market is persistent. However the 5.53% capacity growth in 2016 and OPEC’s recent cut on oil supply in the global markets may bring some recession in the tanker segment in the coming years. There are several reasons for this trend. The most important reason is the synergy of the buildup of a grave oversupply in the fleet and a weakening demand in the supply chains. The losses incurred by ordering and building new ships (at the expectation of turn of business cycles and return of profitability) have been so huge and costly that has led to cancellation of many newbuild orders worldwide. The second reason can be the heavy and unpaid debts of the shipping lines: As a result, the ship finance is seen as a very risky business by the banks and investors and it is generally feared and avoided worldwide. The third reason is the addup of idle or laid-up ships to the oversupply in the market. One significant instance in 2016 was the toxication of the container business by the insolvency of Hanjin shipping that caused the entrance of 620-thousand TEU of idle capacity to the stagnant market.

In this context, the ship building industry does not seem to have a bright future in the coming years. Most of the newbuild orders are being delivered and nearly no new order is made. According to Danish Ship Finance, the number of active shipyards have fell from 1140 in 2010 to 630 in 2016, and 290 other shipyards will be at the verge of closure after 2016.

In this context, the ship building industry does not seem to have a bright future in the coming years. Most of the newbuild orders are being delivered and nearly no new order is made. According to Danish Ship Finance, the number of active shipyards have fell from 1140 in 2010 to 630 in 2016, and 290 other shipyards will be at the verge of closure after 2016.In order to survive the destructive overcapacity trend, the industry took some measures. The classic solutions were slow steaming, and shipping alliances (in container shipping). Yet this solution could not apparently contain the troublesome situations in the middle of 2016. In this sense, the breakup of the ship and shipping companies (in terms of ‘ship demolition’ and ‘Mergers & Acquisitions’) were seen as a contingent solution. We review the ship demolition here and go back to M&A trend in continue.

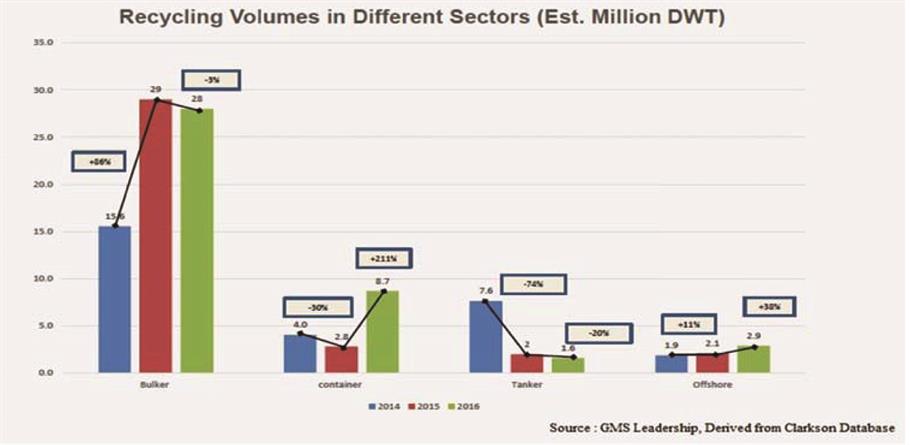

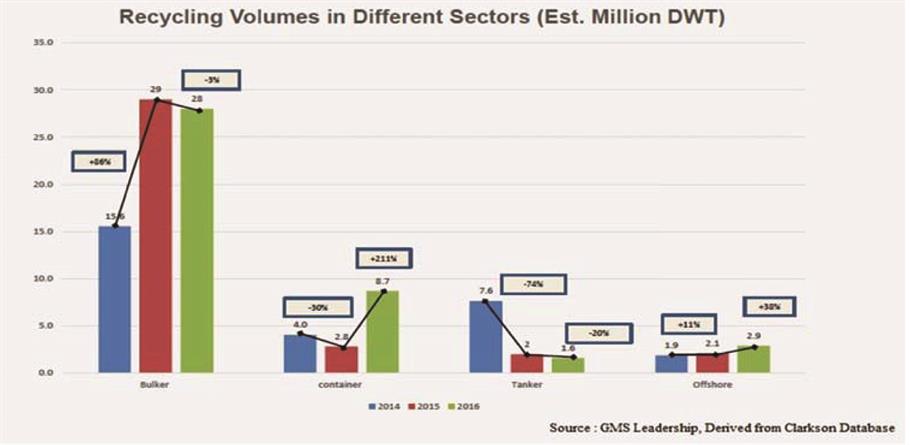

The ship demolition in the 2016 rose significantly as a survival solution in the industry. It has been mainly fueled by:

The burden of idle fleet costs throughout the industry *

* Fundamental changes in the industry infrastructure , especially by inauguration of Panama Canal Expansion project

* Shocking add-up of extra-idle fleet as a matter of unexpected events (i.e. Hanjin Shipping Insolvency)

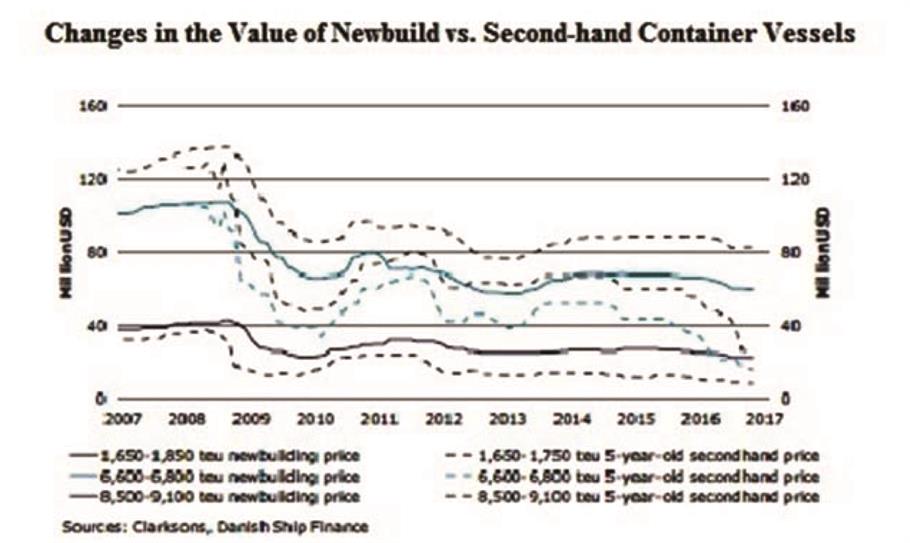

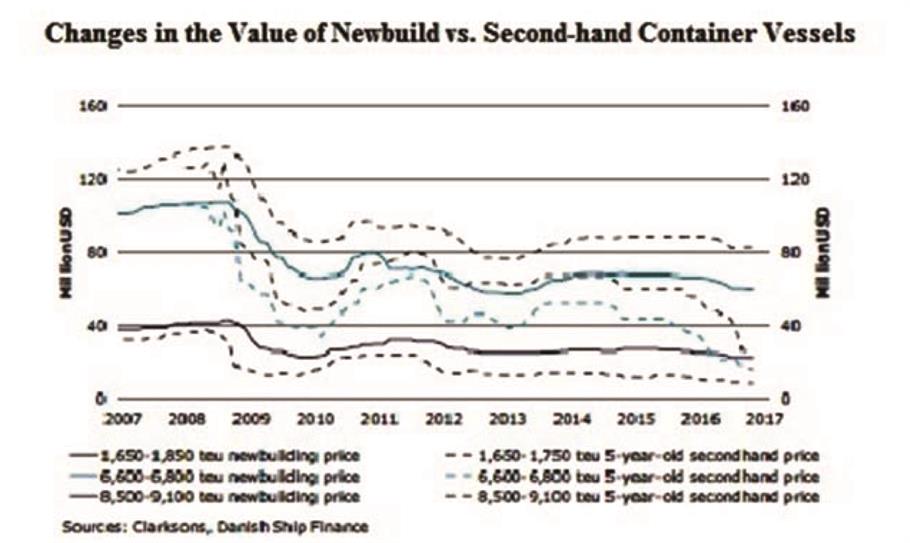

* Free fall of the asset value of secondhand vessels to the level of their residual value in the deteriorated markets

The greatest shock was seen in the container segment where in spite of the expectations for recovery, the ship demolition had a 211% rise. However as expected, most part of demolished deadweight tonnage was seen in the bulkers segment. According to Danish Ship Finance, 40 % of the ships that have been demolished in 2016 were younger than 20 years old. Even vessels with 7 to 10 years of age ((e.g. M/Vs India Rickmers, Viktoria Wulff, and Hammonia Grenada in and early 2017) have been sold for demolition. Within the coming years, the ship demolition will continue as a balancing mechanism until the overcapacity in the fleet is lightened and the industry’s businesses return to profitability.

Freight revenue and profit for ship operators

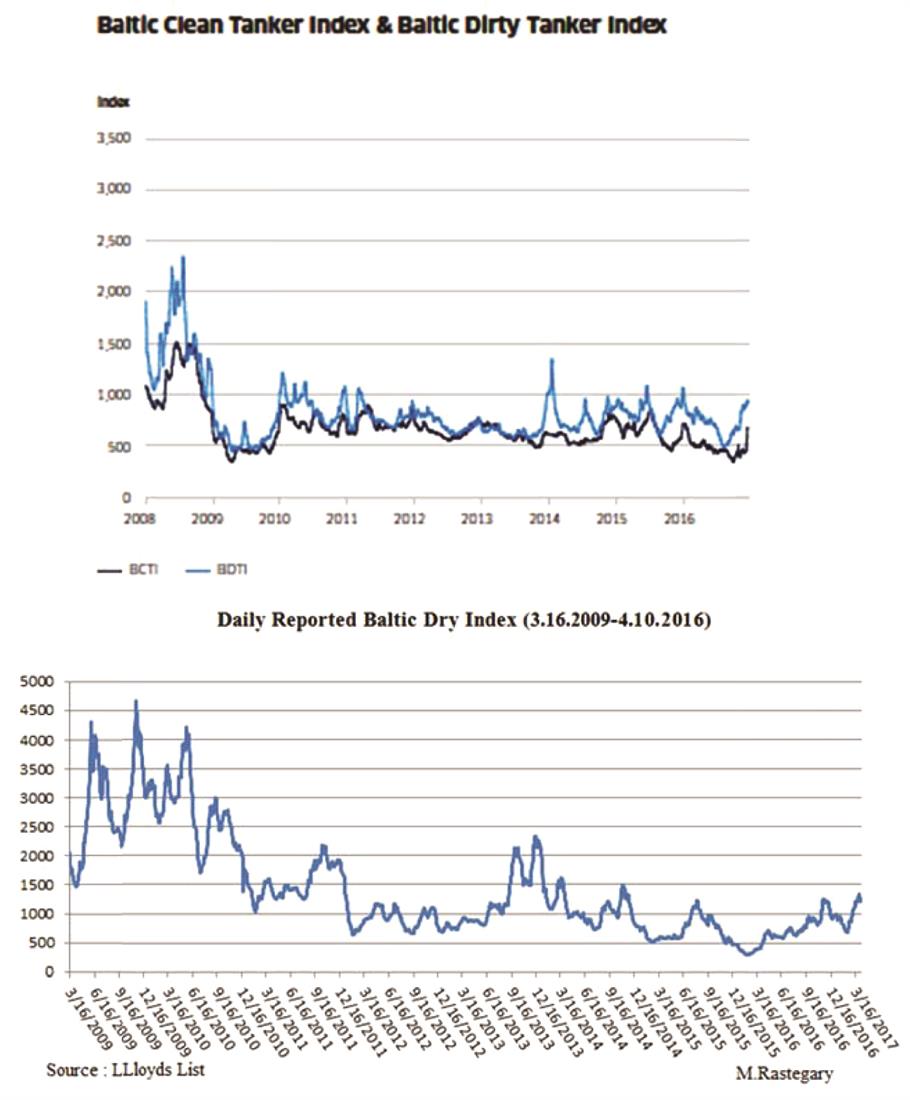

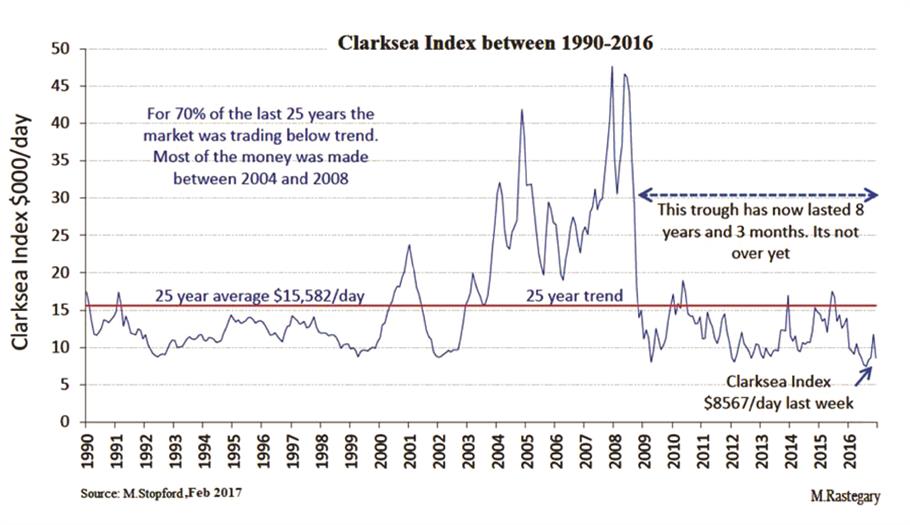

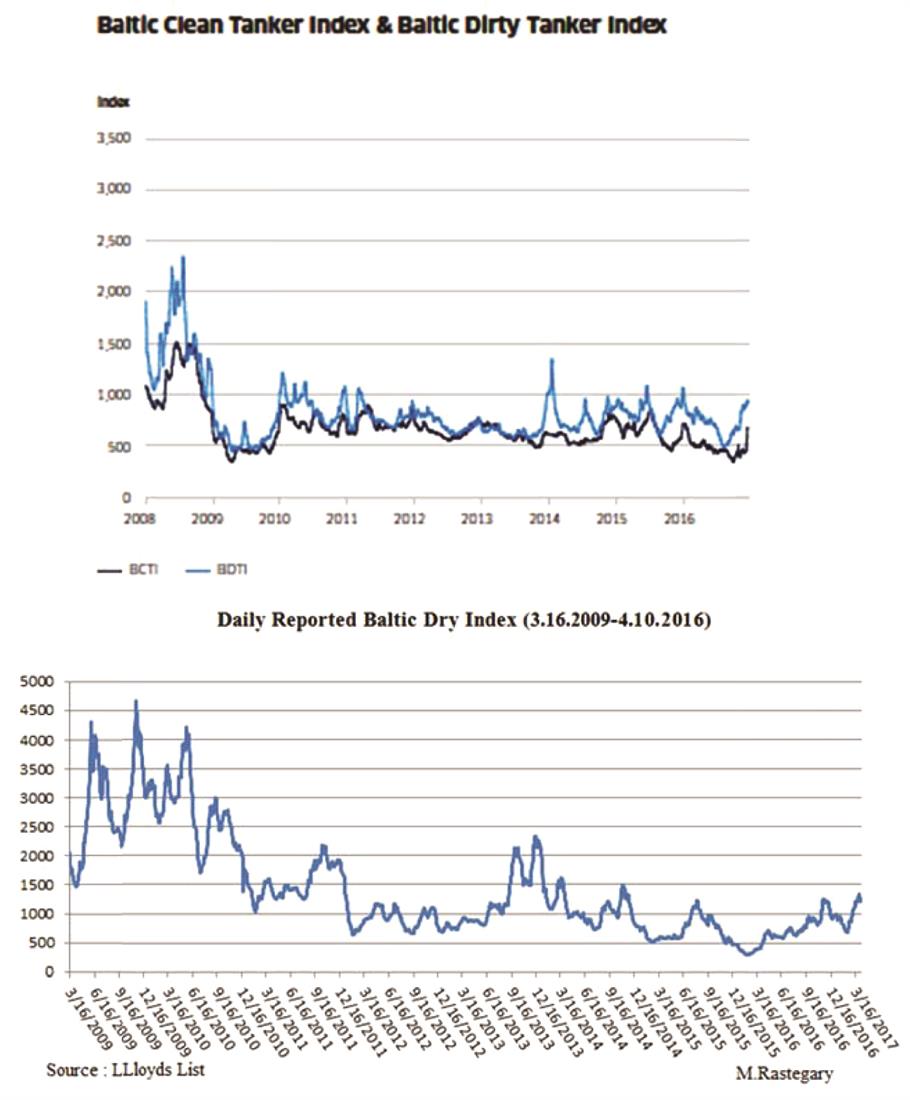

In such a turbulent market, the freight rates in the industry experienced a free fall in 2016. Nearly in all of the industry’s segments, the freight rates hit their lowest record in decades. In the bulk segment, the BDI index fell to 290 in February 2016, which has not been seen since 1985. In the tanker segment, the BCTI and BDTI have shown steady fall of freight rates throughout the year although the fleet has been operating well above their operating costs.

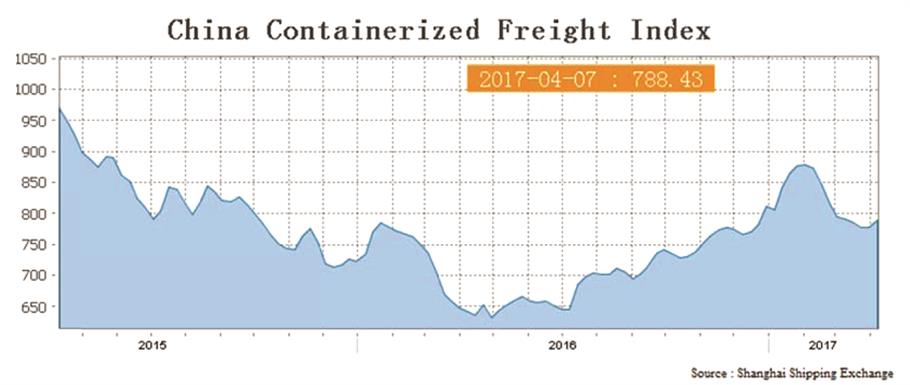

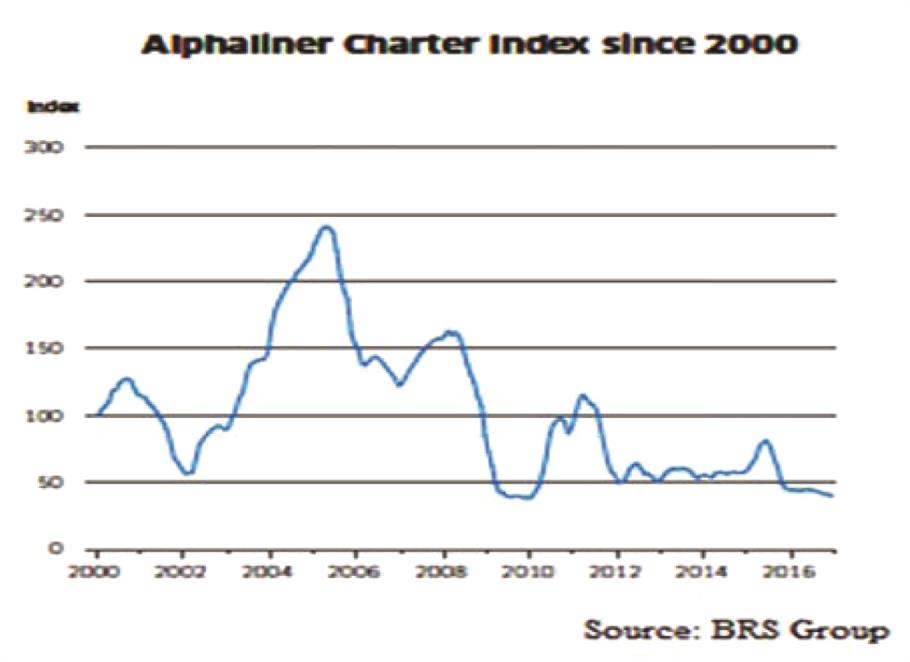

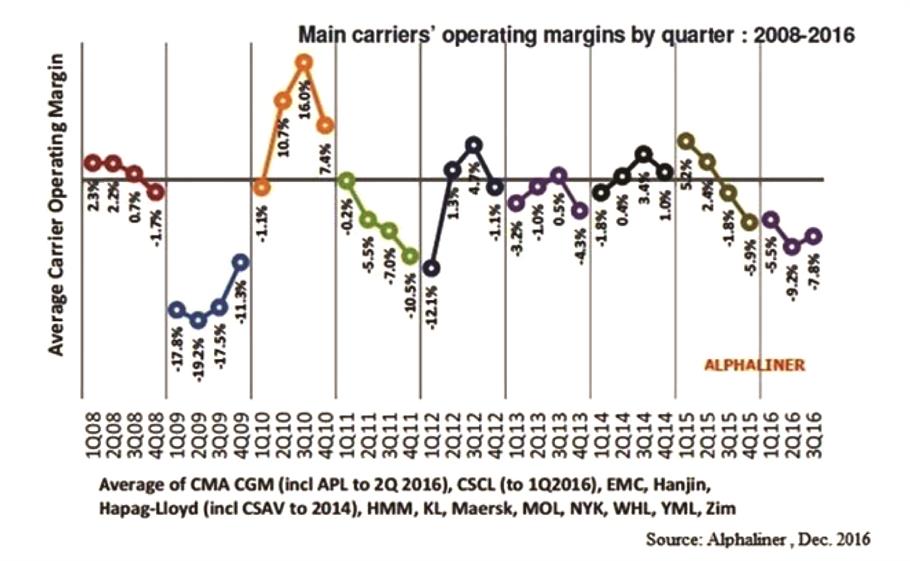

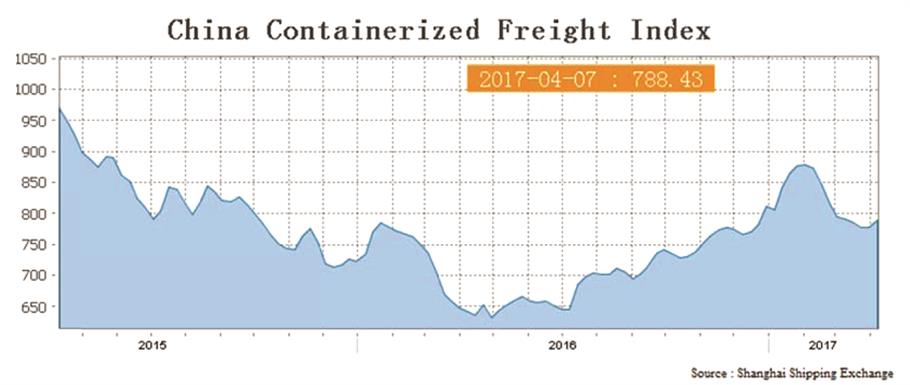

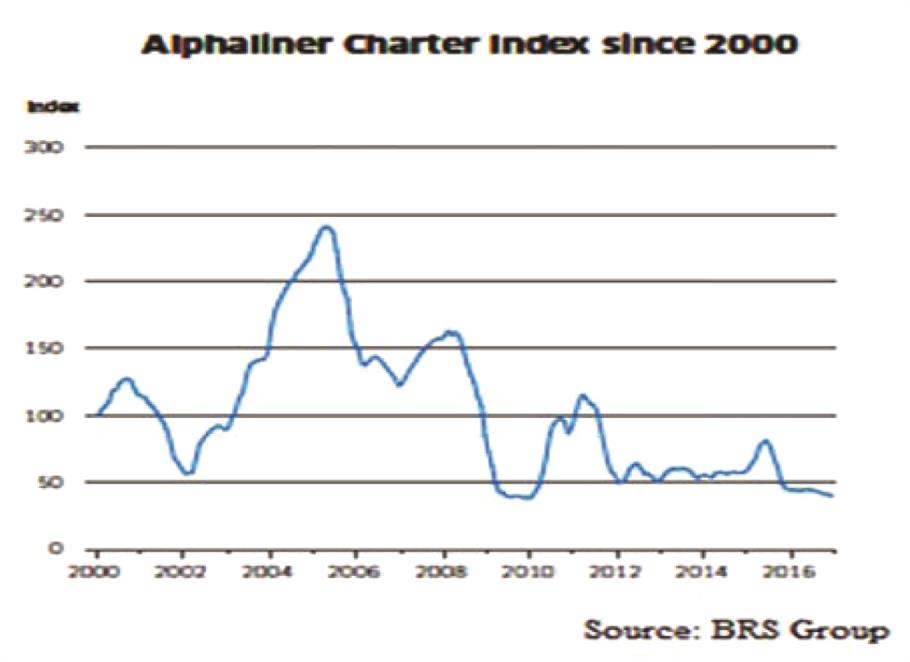

In the container segment, both the freight rates and charter rates were subject to historic downfalls. For instance, in April 2016 CCFI indicated a historic low at 632 points. Also the Alphaliner Charter Index indicates the bearish trend of the cellular vessel charter market at its historic lows.

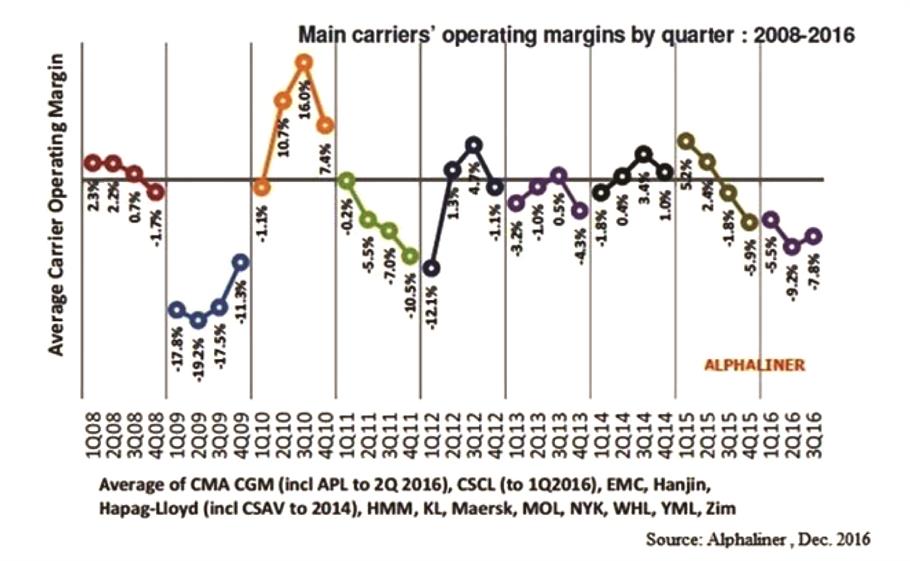

The results of these downturns were catastrophic falls in the freight industry’s revenues. The average earning of a ship in 2016 was estimated to be 9,441 USD which is 34.5% lower as compared to the 2015 figure. One eminent instance of dramatic consequence of such trends can be seen in the disappointing falls in the operating margin of global container carriers after four consecutive years of losses in business.

The most significant impact was the disastrous bankruptcy of Hanjin Shipping as the seventh great container carrier in

the world which as discussed before, gave rise to several other forthcoming consequences in the industry. Nevertheless, the Hanjin Shipping’s bankruptcy case will be always remembered in the industry’s history as a prominent instance of a global carrier’s demise, in spite of its colossal size and market share.

The industry is taking some measures to contain the situation. Along with other measures mentioned earlier, mergers and acquisitions among the carriers have been one of the conventional solutions. In 2016, six major mergers and acquisitions have taken place among the global container carriers. These measures have developed more power and price control in the marketplace through developing a high level of consolidation in the market.

Yet, along with the shipping alliances the organic growth of some shipping lines as a matter of the mergers and acquisitions can have implicit outcomes in the coming years: the global shipping market can transform into a highly concentrated oligopoly that is controlled by a few number of companies. This can have critical impacts on the future of international trade and its stakeholders (including businesses, and nations).

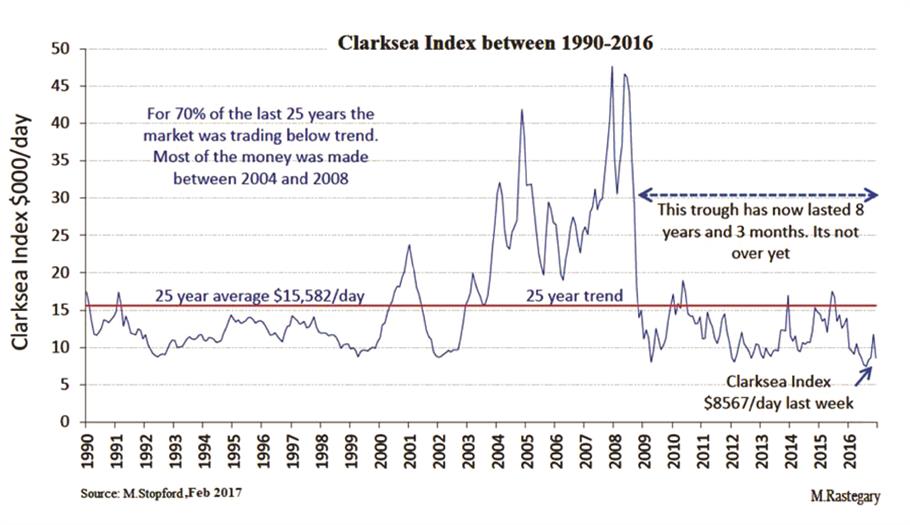

According to the cyclic nature of the shipping industry, the historical low freight and charter rates may imply that the recovery of the industry has begun. Yet the trends indicate that the road to the heights of a prosperous business will be long and bumpy. In this sense, the Clarksea Index can provide some useful insight to envisage the outlook of the industry in the coming years. According to Dr.M.Stopford, the Clarksea index shows that within 17 years of the past 25 years, the industry has been earning less than the average amount of earning in the period. As discussed, within the period the industry has been loaning great funds to invest on her fleet in spite of oversupply and weakening demand in the economic context. It is obvious that the industry needs to change, and the change comes with pain.

The changes are most essential in the business models, technologies, size of markets, market shares and penetration, interrelations of the industry’s businesses (i.e. freight, ship building, Ship demolition, Sale and Purchase), and interrelation with other businesses and stakeholders (banks, insurance, ports, manufacturers, shippers, etc.). These changes are expected to emerge until early 2020s, and in order to survive and develop, the shipping companies shall invest and effort in terms of innovating and/or keeping pace with such changes.

Technology and Regulations

Technology and regulations are two other elements that can affect and shape the shipping industry’s supply. These are the elements that can act towards meaningful change in the attitude, behavior, and performance of the industry.

In the coming years, two sets of regulations will have significant impacts on the supply of the shipping industry. The first set is consisted of the national and international regulations on the business development and international trade. These include the regulations on anti-trust and competition policies, customs, and national and intentional security. The second set of influential regulations on the industry is those that focus on ship emissions and ballast water.

IMO’s Ballast Water Management will come into force in September 2017. This convention enjoys the accession of 52 parties and involvement of 35 percent of the global merchant shipping tonnage. It requires all ships of 400 gross tonnage and above (including all existing vessels except floating platform, FSUs and FPSOs) to possess International Ballast Water Management Certificate (IBWMC). The time consumed in terms of ballasting and deballasting are considered as unproductive times for ships. Moreover, the installation, cleaning and maintenance of Ballast tanks will cost millions of Dollars per ship. Similar regulations are also mandated in some non-contracting states like US with some discrepancies in approval of BWM equipment. The discrepancies include the range of approved systems (currently more than 60 available types) and the approving authorities.

IMO’s regulation for reduction of air pollution ( including SOx, NOx, Particulate Matter, and Green House Gases) is another influential trend that has the potential to develop restrictions and incur huge costs in the industry level. These regulations are mainly derived from chapter IV and Annex VI of MARPOL convention, and include:

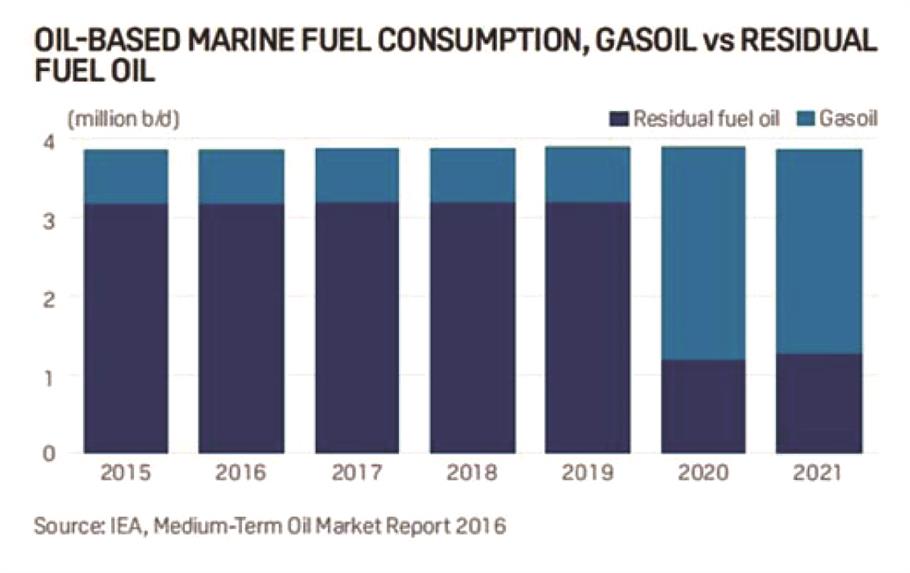

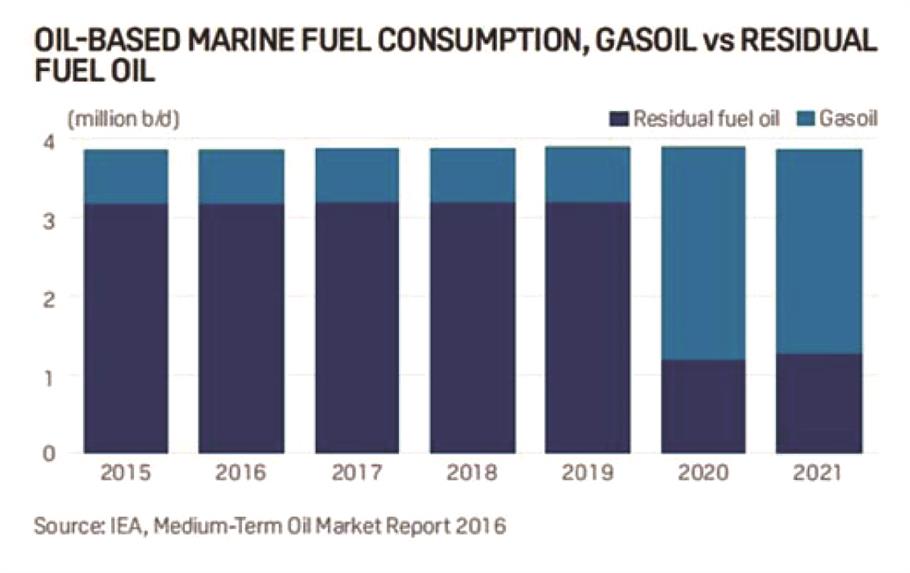

* Reduction of SOx, and Particulate Matter in Ship Emissions- Reduction of SOx, and Particulate Matter are seen as harmful components in ship emissions and IMO is targeting their reduction in the industry. The trend can have significant influences on the maritime fuel production, bunkering, shipbuilding, and most importantly the freight industry. There are two general approaches in the industry: lowering the sulphur content in the maritime fuels, or using exhaust scrubbers to clean the gas emissions from the ship. According to IMO announcement in MEPC70 (Oct.2016) the 0.5% Sulphur cap in the marine fuels will take effect from 2020. This implies a necessary shift in the marine fuel supply from Heavy Fuel Oils to Marine Gas Oil.

It is estimated that 19% of the ships will be equipped to scrubber systems (which will have some negative effects on GHG emission), and the rest will have to use MGO. The result will possibly be a sharp rise in MGO price (with high demand and insufficient supply) and a steep fall in the prices of the HFO (with a much lower demand and abundant supply).In the same context , the ships will be in need of higher credit levels for procurement of their fuel, and the bunker suppliers will need to involve more liquidity to stay in the course of business. The Sulphur cap is expected to cause dramatic cost increases in the costs of shipping companies. For instance, in 2016 International Transport Forum OECD has estimated that the implementation of the 0.5% sulphur cap a can bring a cost burden of 5 to 30 billion USD to the container shipping.

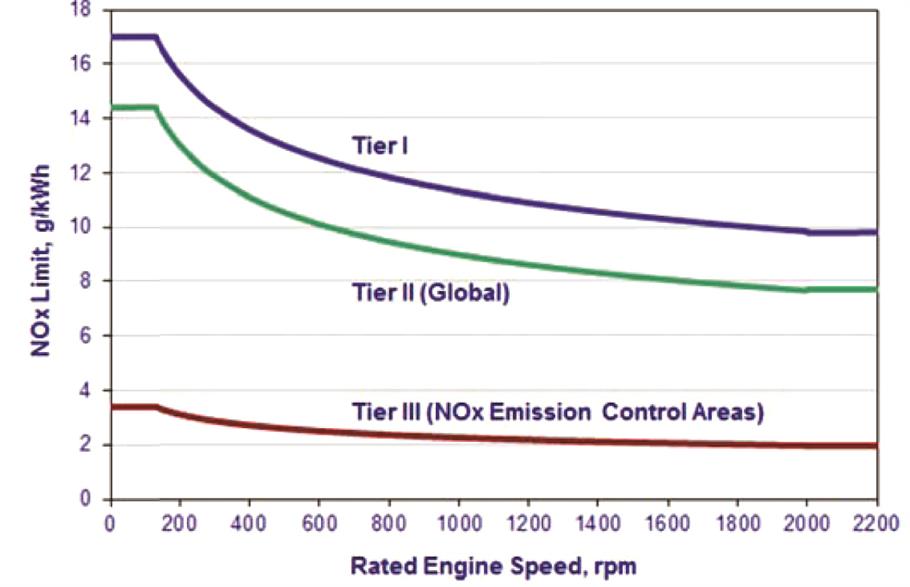

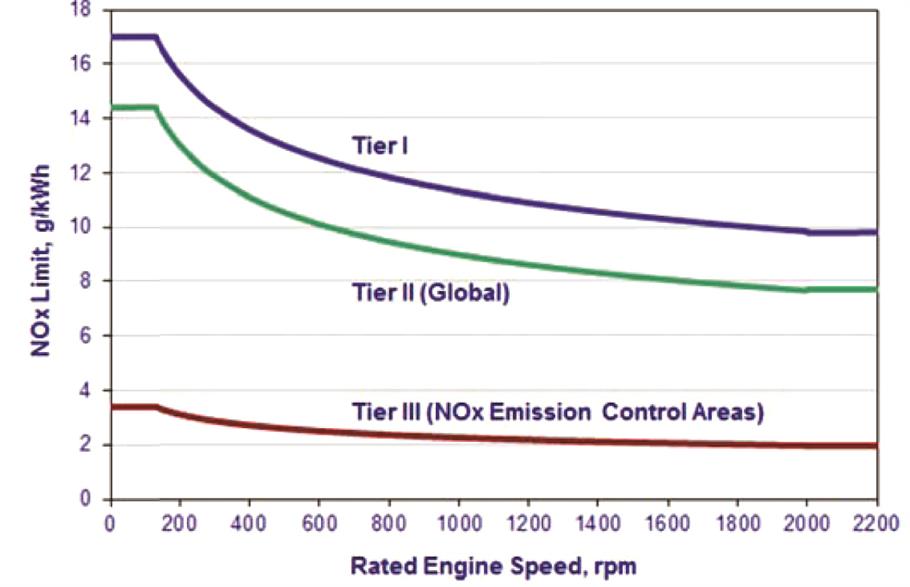

* Reduction of NOx in Ship Emissions- by increase of MGO, reduction of NOx emissions from ships will find more significance. The NOx emission control is based on a 3-tiers scheme that establishes the NOx emission limits in ships based on the date of the engine design. Tier I and Tier II limits are global, while the Tier III standards apply only in NOx Emission Control Areas.

* Tier II standards are expected to be met by combustion process optimization while the Tier III standards are expected to require dedicated NOx emission control technologies such as various forms of water induction into the combustion process (with fuel, scavenging air, or in-cylinder), exhaust gas recirculation, or selective catalytic reduction.

NOx emission limits in Annex VI of MARPOL convention

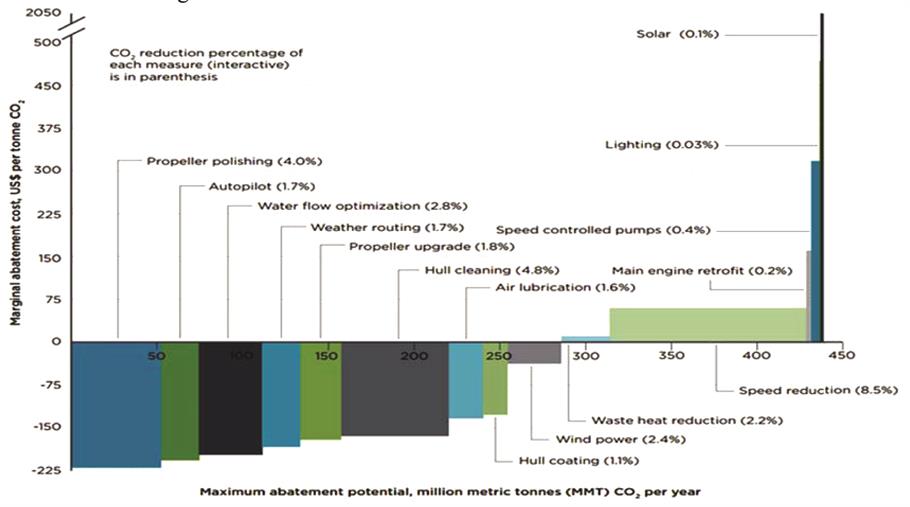

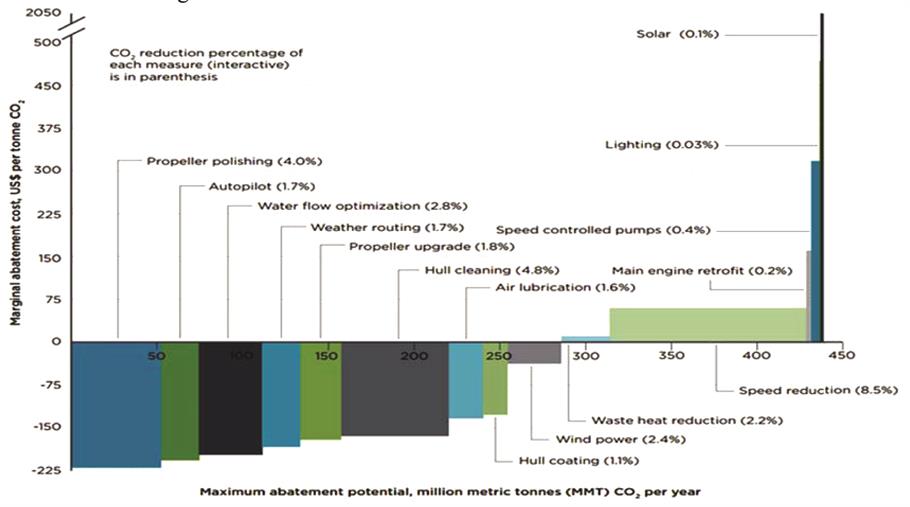

* GHG Emission Abatement – The ‘Comprehensive IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships’ is being developed between 2017 and 2022 and the needed GHG reduction requirements will be concluded for entering into force from 2023. The results will entail a number of capital-intensive modifications and/or utilization of technologies in the ships. The figure below indicates a number of technologies that are considered as solutions for GHG abatement.

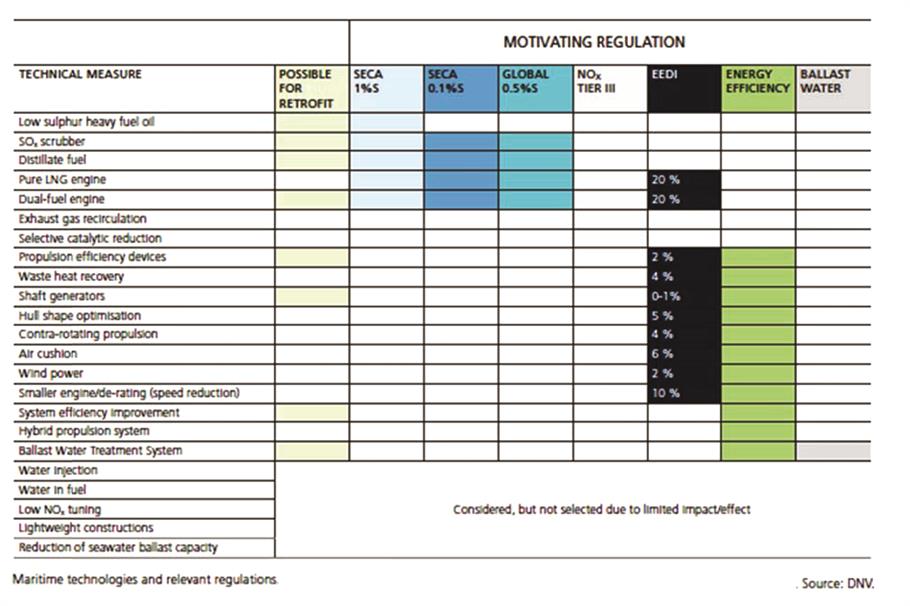

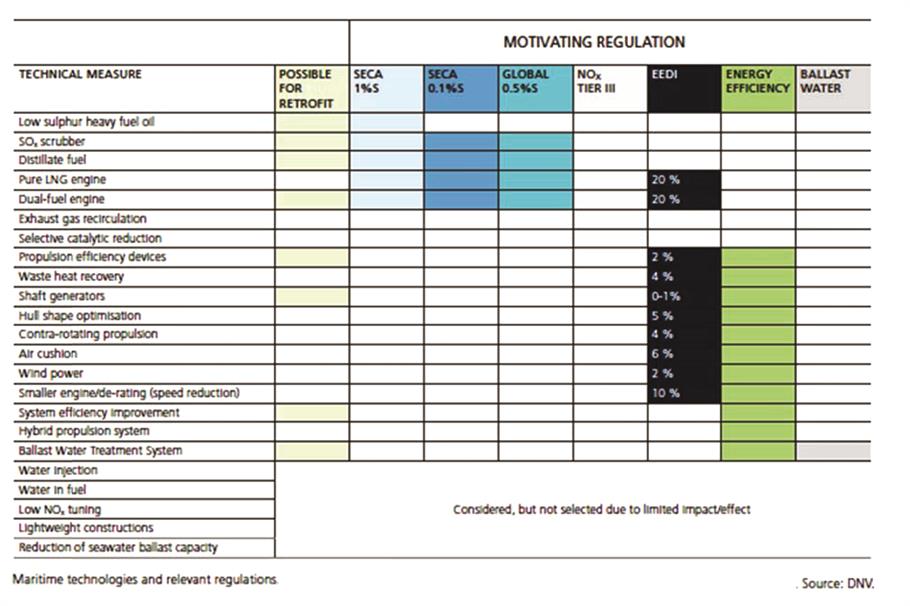

The following table provides a number of maritime technologies in the field of energy efficiency and environmental protection and their relevant regulations. As seen in this table, in many cases none of these technologies can provide complete compliance with the regulatory requirements, and therefore it is expected that appropriate mixes of them are utilized to fulfill the compliance.

Although the environmental regulations are enforced globally, they are encountered by many political acts by some states, unions, and NGOs. Among these acts, we can point to new US government approach towards climate change and fossil fuels. For instance, one outcome of such an approach was the omission of the ‘climate change financing’ in the final statement of G-20 in 2017. Therefore, it is highly possible that international controversies emerge around sustainable development and environmental management policies in near future. This can affect the shipping industry by providing more time for adapting to the new conditions and requirements.

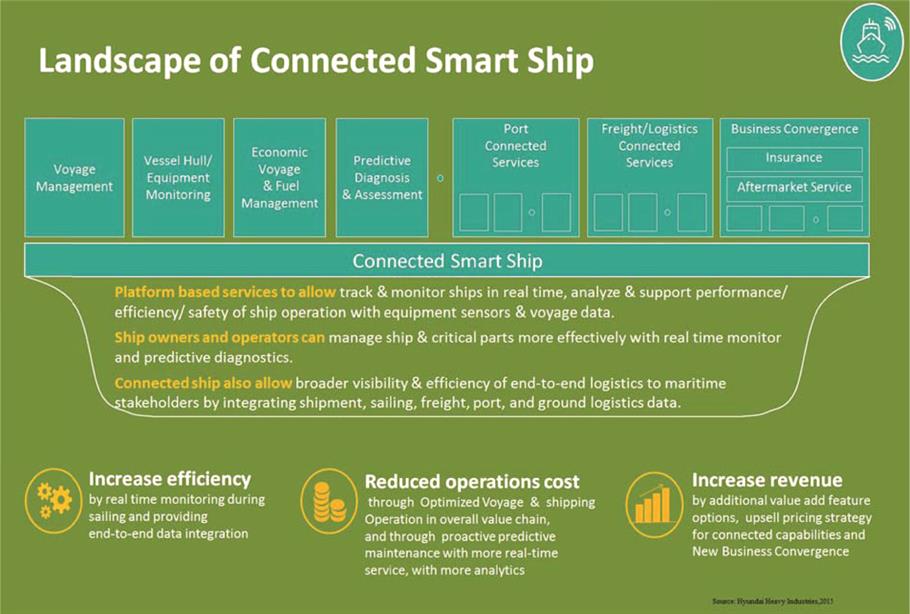

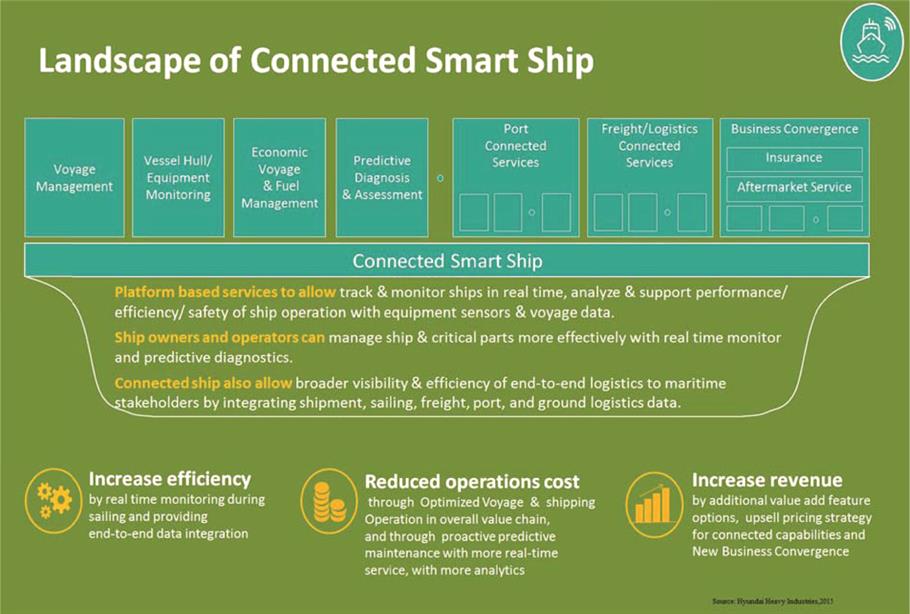

Aside from the technologies that serve the regulatory compliance purposes, the industry is also the scene of technological developments towards enhancements in the industry’s productivity. These developments are seen as the hopes of the industry to overcome the myriads of issues and challenges that are troubling her businesses. The Smart Ship concept is one of the prominent instances of such technological development.

Smart Ships incorporate Information and Communication Technology to develop intelligence in the ships that act as the Strategic Business Units of the shipping line. The intelligence is established by use and interplay of various technologies onboard, onshore, and satellite-wise. The spectrum of these technologies includes telematics, data storage, analytics, satellite communication, industrial automation, applications, and information systems. The synergistic interaction of such systems on a ship can provide:

* Automation of many processes onboard – This can encompass a wide range of functions and processes including navigation, preventive maintenance, engine and propeller control, trim optimization, collision monitoring, hull tension monitoring, etc.

* Standardization and digitalization of many outgoing and incoming information flows – documentations, regulatory reports, digital logs, environmental data, economic data, etc.

* Connectivity-enhanced processes and functions- weather monitoring, route optimization, remote engine monitoring, port sync navigation, cargo trace and track, etc.

Moreover, it is said that smart ship concept can revolutionize the business models of the shipping industry. For centuries, ships have been managed as discrete and remote business units with autonomous and independent management. But the smart ship is intelligent and connected. It can perform many of her functions automatically, and many of its functions can be managed, operated (or at least monitored) by teams thousands of miles away in an office or even another ship. This builds the capacity to move the fleet management to the next level: Integrated fleet management. In this sense, the shipping company can manage both the fleet and the business more efficiently and seamlessly by reliance on the real-time data and direct connection with the personnel and even systems of the ships. This can lead to great efficiency improvements and savings in business planning, business leadership, Human Resources Management, engineering, maintenance and repair, customer relationship, safety and security, etc. This is especially important for the big shipping companies that are growing larger and larger in size and need to enhance their business administration in line with their organic growth.

The connectivity of smart ships can also be used to develop more integrated relations with stakeholders in the value chain of shipping. It can be used to connect the ship (and her operator) to the shipowner, shipbuilder, port authorities, terminal operators, shippers, cargo interests, etc. These integrated relations can provide many opportunities for engendering added value.

There are several other emerging concepts in the industry, among which we can point to the Low Energy Ship, the Arctic Ship, the Green-fueled Ship, the Electric Ship, the Virtual Ship, and many more. Most of these concepts are oriented towards quality improvement, energy management, pollution control, safety, security, and cost savings.

Conclusion

The shipping industry has been moving in turbulent waters for years and in spite of some slight improvements, it seems that the harsh and tempestuous conditions will not change much in the near future, This situation is a result of strategic mistakes in terms of assessing the global demand and balancing the supplies of the industry with it for nearly two decades. In the recent years, the supply of the industry is getting right-sized automatically by the demand-driven market conditions.

According to the cyclic nature of the shipping industry and the groundbreaking low records of the industry in 2015 and 2016, it can be anticipated that the industry will pick up a slow recovery trend that can take the industry back to their peak in early 2020s. Yet, the costs of compliance with regulatory requirements for air pollution control and energy efficiency may be disruptive to the industry’s recovery trend.

In these years, the markets of the industry will be more concentrated and under the control of much bigger and stronger firms. The new marketplace can turn into a perilous place for the interest of many stakeholders of global supply chain, including the nations and the states. Therefore specifically in the national level, it is essential to have a policy for shipping that can protect the national interests of the state. In terms of Islamic Republic of Iran’s resistive economy, this should include renovation and empowerment of the national shipping fleet to maintain the state’s international trade.

It is obvious that the yesterday’s solutions are not usually appropriate for resolving the problems of tomorrow. This is the inappropriate attitude that has afflicted the shipping industry in the current state. Indeed the industry is in intense need of innovations to overcome her issues. Such innovations are most needed in management, business administration, and technologies. It is essential to understand that only a number of those shipping lines will survive and grow in the disruptive conditions of the current market that are able to learn to react, and innovate to proact in the face of all encountered challenges and issues.

By: Mehdi Rastegary

Sina Ports and Marine Services Co.